Tips for Emerging Photographers

Magnum’s Education Director shares insights to help early career photographers to develop their practice

Magnum is known for the work its photographers produce, from the iconic shots in the vast archive stretching back to the 1930s, through to recent achievements, such as covers for the likes of TIME Magazine, or highly respected prizes, such as Susan Meiselas’s recent Deutsche Börse win. But beyond these blockbuster achievements, there is a real desire within the agency and amongst the photographers to pay it forward to a new generation through our educational programming, as well as our new online education platform Magnum Learn.

Magnum’s Global Education Director, Shannon Ghannam, has seen first hand the lessons to be learned from the leading photographers in their field. Here, she offers some insight and practical tips for young or emerging photographers to develop their practice in today’s photography landscape.

As a former student photographer, I regularly pinch myself knowing that I work at Magnum Photos, with some of the best photographers, colleagues and industry experts, and teaching and learning with emerging photographers around the world. Here are some of the key lessons I have learnt that can be helpful to aspiring photographers.

Understand the context

Study the work of other photographers – the masters and your contemporaries, read photographic theory and online debates, understand how visual communication and culture work, and the wider context you are making and presenting work in. Not only is it interesting, it is the foundation for making informed, relevant and engaging storytelling.

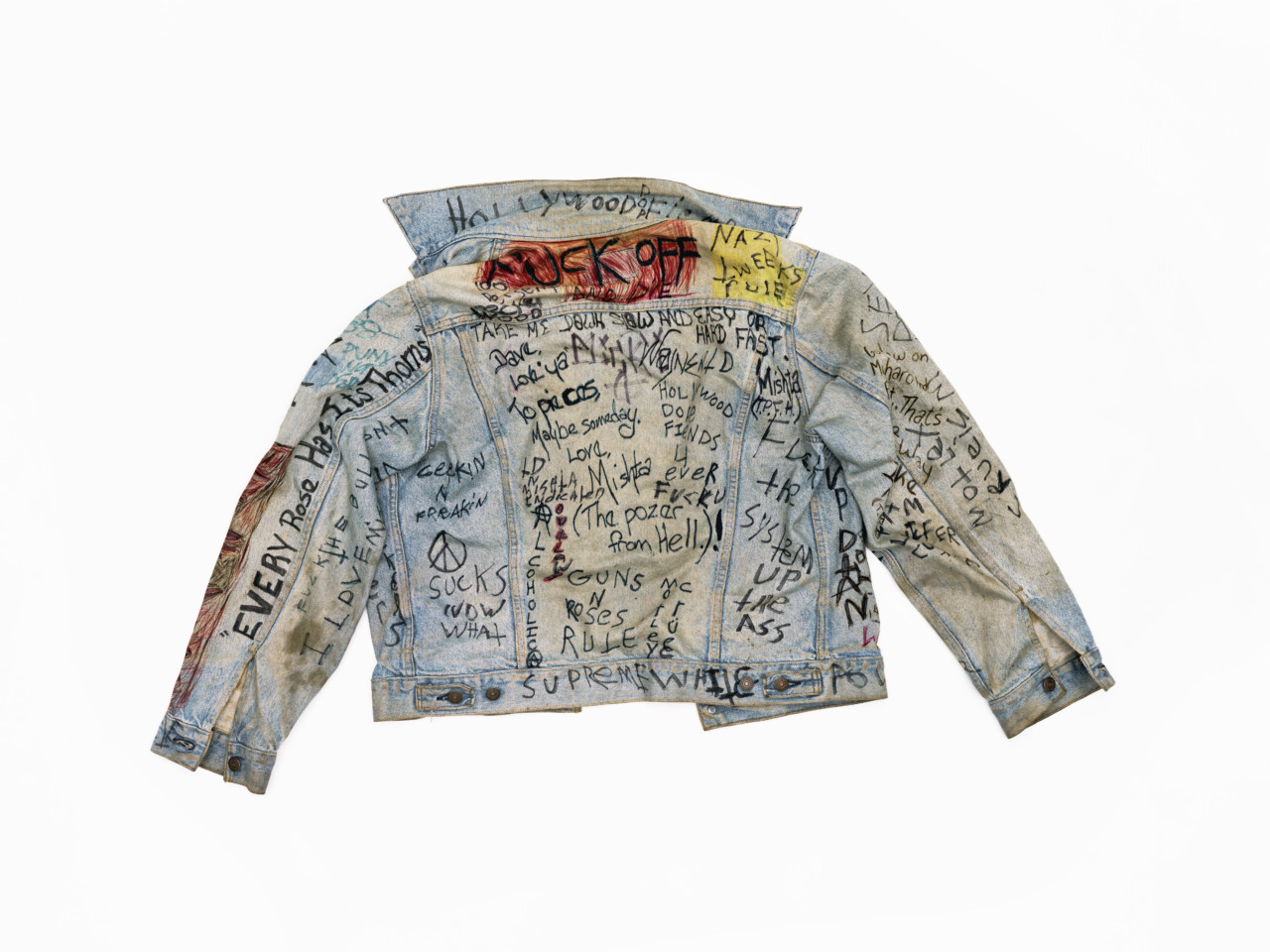

I remember as a first year photography student discovering Raised by Wolves by Jim Goldberg in the library. The long-term, collaborative storytelling felt so very different to the more journalistic, black & white reportage that I had seen up until that point. Jim’s work transported me to the streets of Los Angeles and San Francisco and helped me to connect with the stories of the young people he was photographing through objects, archival imagery and handwritten text. Five years later I wrote my dissertation on collaborative photographic practices and representation after embarking on my own collaborative portraiture project with refugee women and girls from the Horn of Africa living in Brisbane. Raised by Wolves continues to inform my thinking about photography today and I love sharing it with students who are yet to discover it.

Find your own voice

The best photographic work feels like something we have not seen before, whether that is a story, a style or a feeling that it evokes. When conceiving a project, ask yourself the hard questions about why you have chosen this story: Are you the best person to tell it? What are you adding to the genre, or the story, that has not been said or done before? Why do you care and how are you going to make an audience care? Give yourself a head start and choose the project or the approach that helps you answer these questions well.

A great example of this is Tim Hetherington’s ‘Sleeping Soldiers’, a profound study of U.S. military soldiers in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley, which was presented as a multi-screen multimedia project. I remember seeing this work for the first time and being struck by how revealing and insightful the work felt. Tim’s friend and colleague, journalist Sebastian Junger, shared some of the late photographers thought process in a recent Magnum article on the work. He said: “What he said to me was, ‘Look, this is how their mothers see them, they don’t have their gear on, they’re like these little boys and you never get to see soldiers the way their mothers see them. And here they are asleep, innocent, unguarded… They’re pretty big boys mostly.’ That was his brilliance, to see what others were missing.”

Do you

Don’t think you need to show a client that you can do everything. Clients want to see clearly who you are as a photographer; they will be looking for a style or approach that will best suit the project they have in mind. Every emerging photographer needs to have a personal project that shows what you are capable of, that expresses what you’re about. This may take years to develop but it will be the launch pad for other commissions and will help cement your individual identity as a photographer.

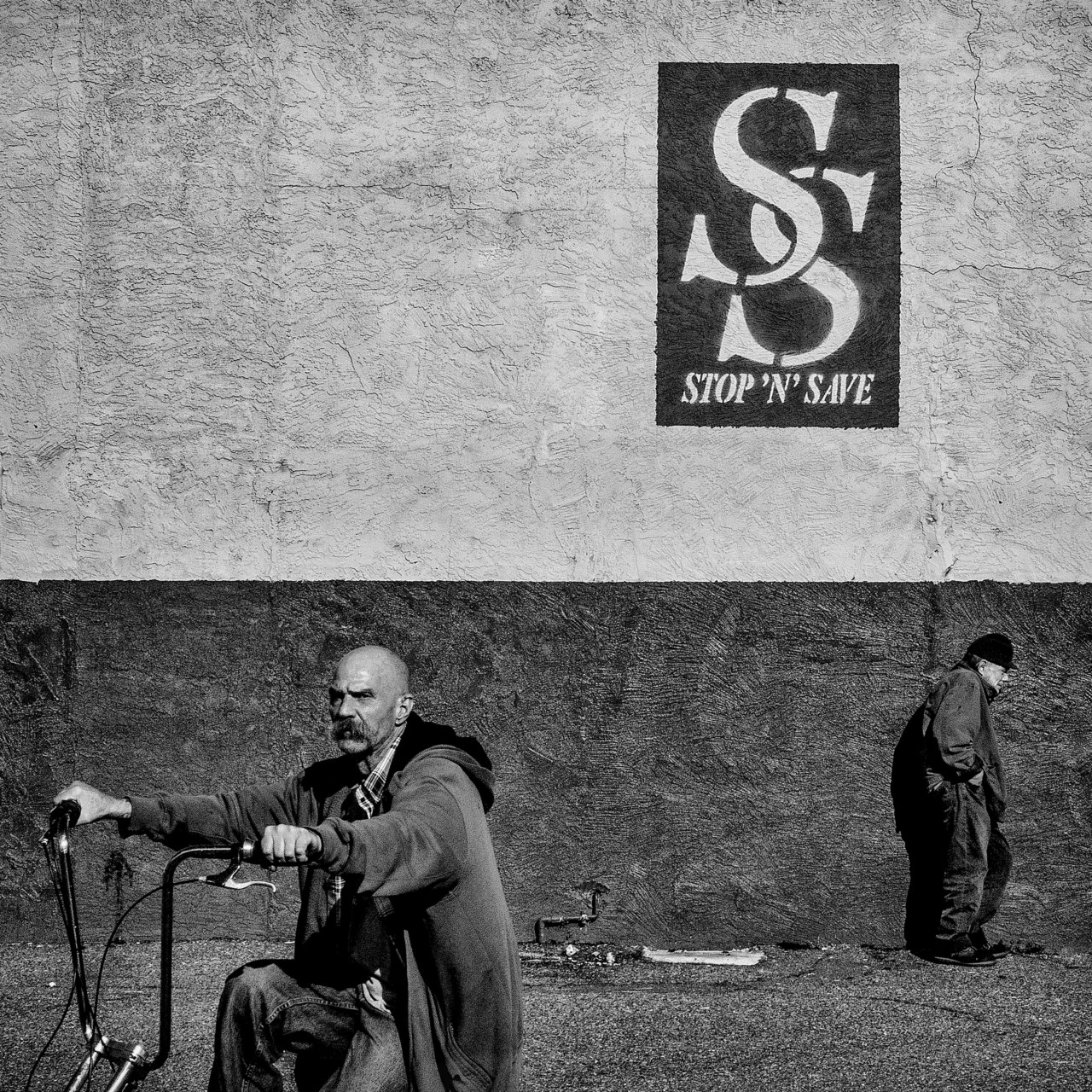

One of the clearest photographic visions of recent times, I think, is the work of Magnum nominee Gregory Halpern, in particular his beautifully realized book ZZYZX. I have lost count of the number of times I have suggested to a student grappling with a problem to look at his work, there is so much to learn about visual storytelling on every page.

Ask yourself what will sustain you photographically

Photograph the thing that you are obsessed with, the thing you are angry about, that you are fascinated by, that you want to understand. Make sure it is something that will sustain you photographing it over many years. The best photographic projects develop over time. Every photographer should have a project that they are chipping away at around other work.

Many years ago I spent an afternoon having a beer with Trent Parke on one of the main streets in central Sydney. Parke’s book Dreamlife is a personal favourite of mine, and a love letter to Sydney, it’s people and it’s striking light. We sat in a window of the pub, talking about life and photography and waited for the perfect light to hit the street corner opposite. Mid flow in the conversation, with one eye always on the corner, Trent jumped up, downed the end of his beer and headed out into the long, late afternoon light. A beautiful example of the passion and patience needed to make great work.

Do the work!

Do the work then spend time sharing it, selling it, promoting it, entering awards etc. There is no way to get around this part. Get comfortable with the fact that making good work takes time. When you are hustling, it can feel like a very lonely, thankless pursuit. Keep at it.

If ever you are in need of some inspiration, check out ‘Geography of Poverty’ by Matt Black, who, since 2014, has taken four cross-country trips over 80,000 miles throughout 46 states of the United States, photographing communities living below the poverty line. The work is a master class in what is possible through sheer commitment and many miles of road.

Go where your audience is

The making of a book is a beautiful way to get your work out into the world, but it is not the only way. What impact do you want your work to have? Who needs to see it to have this impact? Where are they looking? How can you reach them?

One way of reaching a large audience and building a community is Instagram. In a Magnum article in which our photographers offered their tips on how to get the most out of the app, Christopher Anderson said: “In my case it was important to be on Instagram because it has become such a fulfilling and fun creative outlet. I am able to look at, think about and take pictures with a freedom and immediacy that is more difficult with my ‘work’.”

Build a community

Photography can be hard and lonely. Build a community around you. Reach out to people whose work you like on Instagram. Organise a meet-up. Attend a workshop. Be generous with your time and ideas, help others and others will help you. Many of the participants we have met through our global workshop programme have kept in touch, formed their own networks and even started their own collectives.

Expand your practice

Photography is just one tool in a storytelling kit. How an audience understands and feels a story is in your hands. Whether that is a choice of frame for your exhibition, paper for your book, music for your multimedia piece, and edit of your accompanying text, every single choice you make is a chance to make the work sing. The job does not end in the camera.

One of my favourite examples of this is ‘1915’ by Diana Markosian, who worked with survivors of the 1915 Armenian genocide to retrace their flight from Turkey and capture their lost homeland through pictures, video, drawings and exchanges between the subject and the photographer, all documented and presented in a compelling and deeply moving web presentation.

Kill your darlings!

Editing is crucial. If you can’t be brutal with your own images, find someone you trust who can. If you are working on a project over a long period of time, you will edit out many “good pictures”, but the overall work will become better for it. You can read an article that takes you inside the editing process of Magnum photographer Mark Power on Magnum here.

Break the rules

Read the rule book, then throw it out the window. Listen to all of the advice, and then do what you think is best for you and your practice. This singular, dogged approach is a hallmark of the best, pioneering photographers, and it is how the medium evolves.

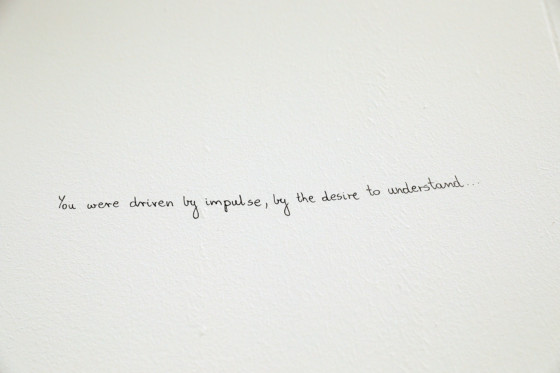

One of the most groundbreaking works I have seen recently is the collaborative project ‘Agata’ by Bieke Depoorter. Bieke met Agata while shooting in Paris as part of a Magnum Live Lab, and their relationship and the body of work they have made together has built over time, unpacking many of the paradoxes of photographic representation.

Of including Agata’s writing on the walls of a recent exhibition of the work Bieke said: “I want her writings to be included because you see how she feels and how she plays with reality.” She added that the writing reveals how photography itself is defining and altering their relationship. That Agata is changing because she is being observed, photographed, and that the process of being the subject is changing how she sees herself. “The picture is not the truth — and I am searching too. We try to find this out together.”

Enjoy the journey

In a recent interview with Magnum on her love of musicals, nominee Cristina de Middel said, “Photography can be playful and propose more questions than it gives answers. That’s the greatest thing photography can do – raise questions.”

It won’t be easy, but it certainly won’t be dull, and that is the magic of a life lived through photography. Enjoy the journey!