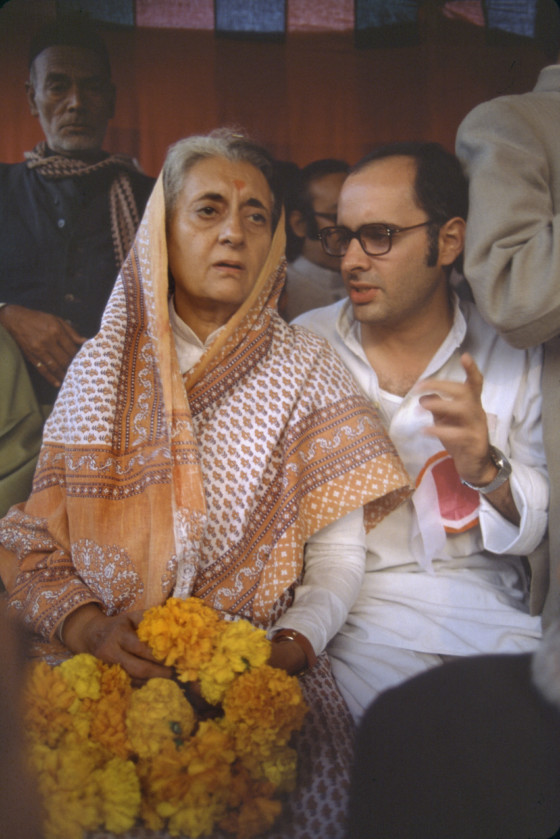

Indira Gandhi: The Centenary of India’s First Female Prime Minister

Portraits of the late Indian leader offer a unique glimpse of one of the most influential women in history

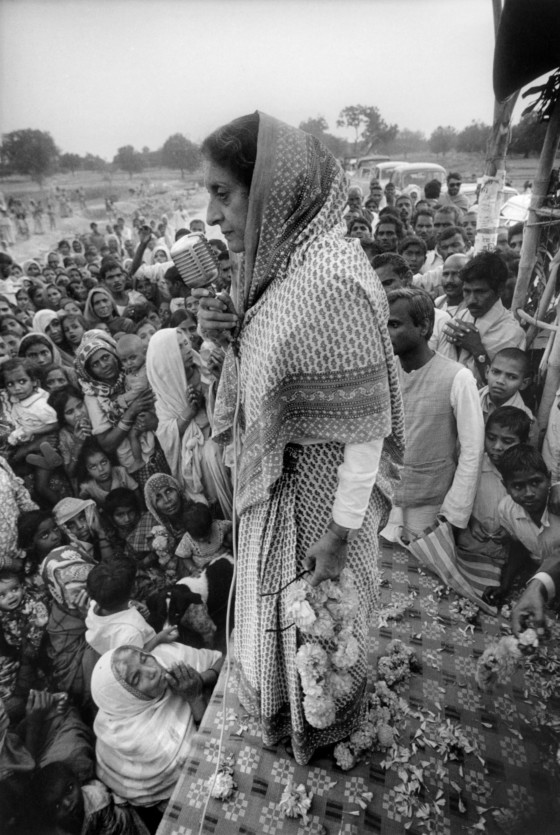

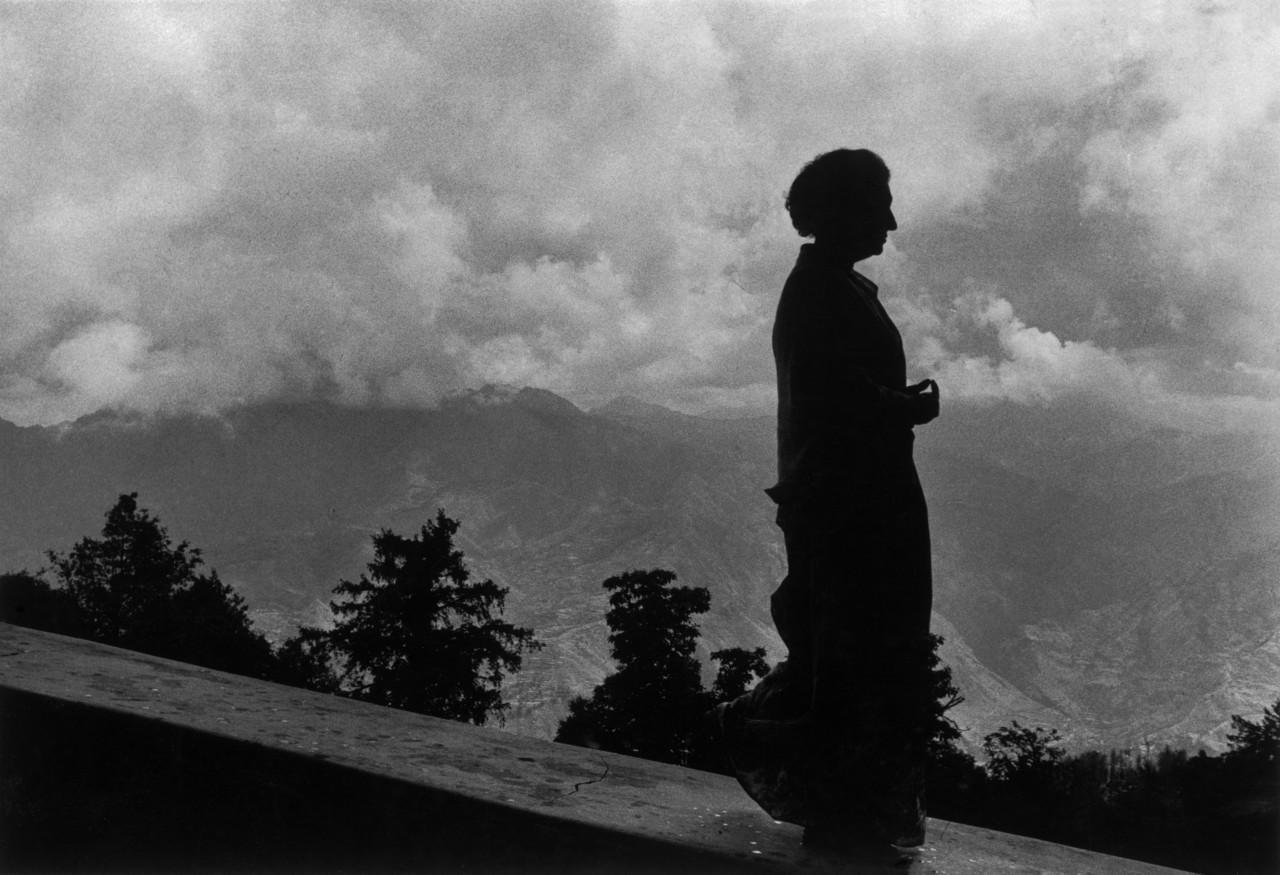

Speaking at a rally in October 1984, Indira Gandhi delivered her own epitaph in a speech: “I am alive today, I may not be there tomorrow…I shall continue to serve until my last breath and when I die, I can say, that every drop of my blood will invigorate India and strengthen it.” A few days later, India’s prime minister was shot dead, assassinated by her own bodyguards, during a morning walk through her gardens.

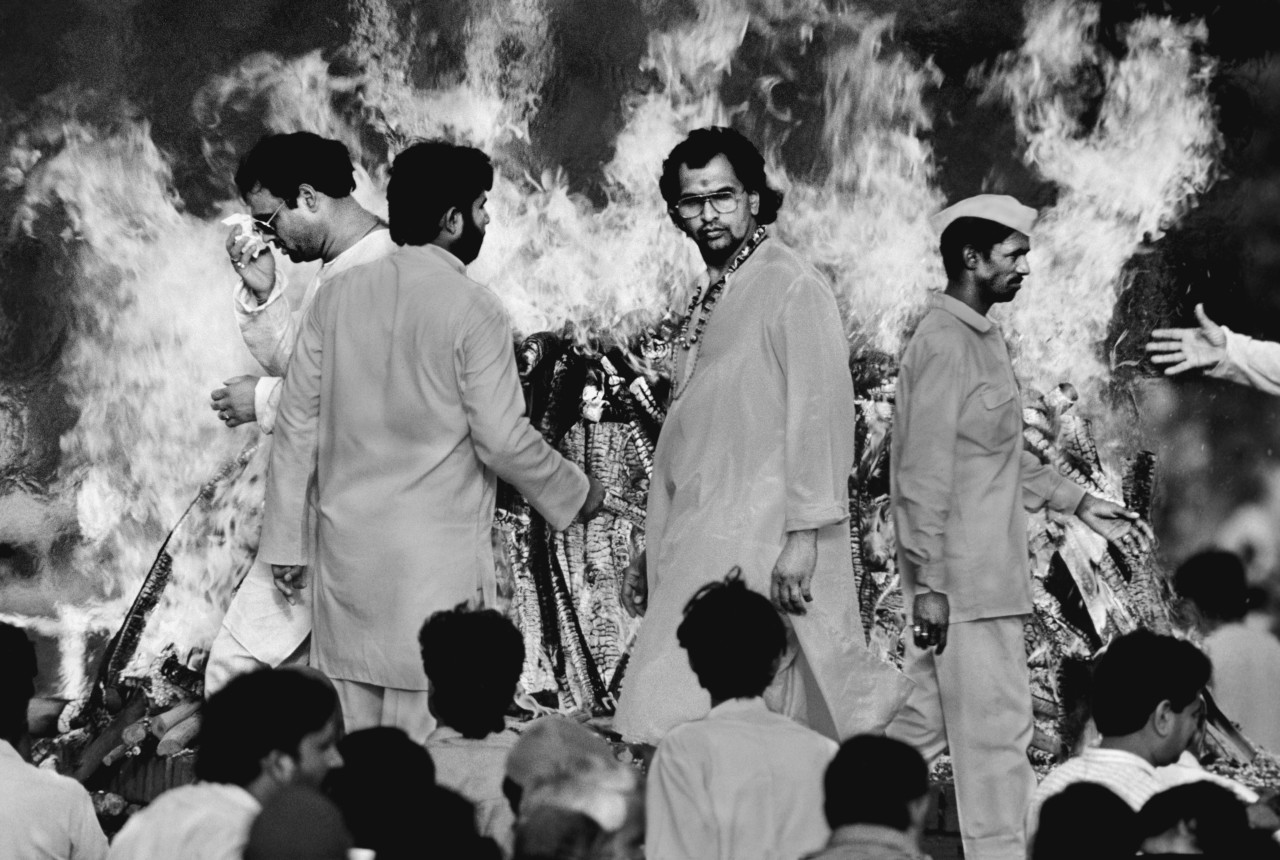

Magnum photographer Raghu Rai captured Mrs Gandhi upon her funeral pyre. It was the last of many portraits Rai had shot over the prime minister’s political career. “I was photographing Indira Gandhi almost every other day from 1967 onwards when she became the prime minister. Indira Gandhi was at the peak of her career and in a certain way her growth coincided with my own” the photographer describes in his book Picturing Time, “there was nobody else in the Congress as strong-minded and as powerful as her”.

"There was nobody else in the Congress as strong-minded and as powerful "

- Raghu Rai

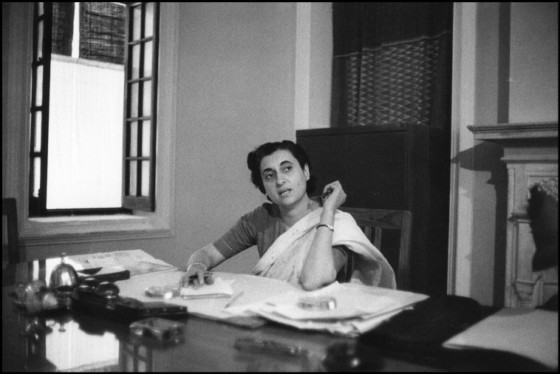

Indira Gandhi was India’s first and, to date, last female prime minister. The only child of former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Gandhi was destined for politics. When Magnum co-founder, Henri Cartier-Bresson first came across Gandhi in 1947, she was at the side of her father as his aide. It was the year India claimed independence and Nehru had been sworn into office – and Indira Gandhi was already drawing up political plans of her own.

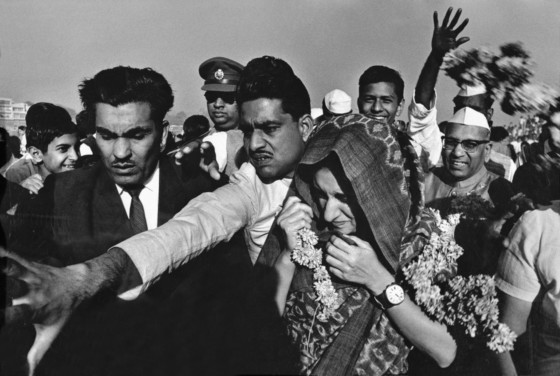

After her first election in 1966, Mrs Gandhi’s popularity soared with her ‘Green Revolution’, a programme fostering self-sufficiency in food production, and later, her role in taming the Pakistan war, which subsequently lead to the formation of Bangladesh in 1971. Devoted to a democratic, secular society in which no caste or religion could discriminate against or dominate others, she had inherited the left-leaning ideals her father had adopted, largely from Marxist tenets. Her pragmatic manner of office had gained her a formidable reputation for being incorruptible. However, being a woman in political life meant she faced unique challenges.

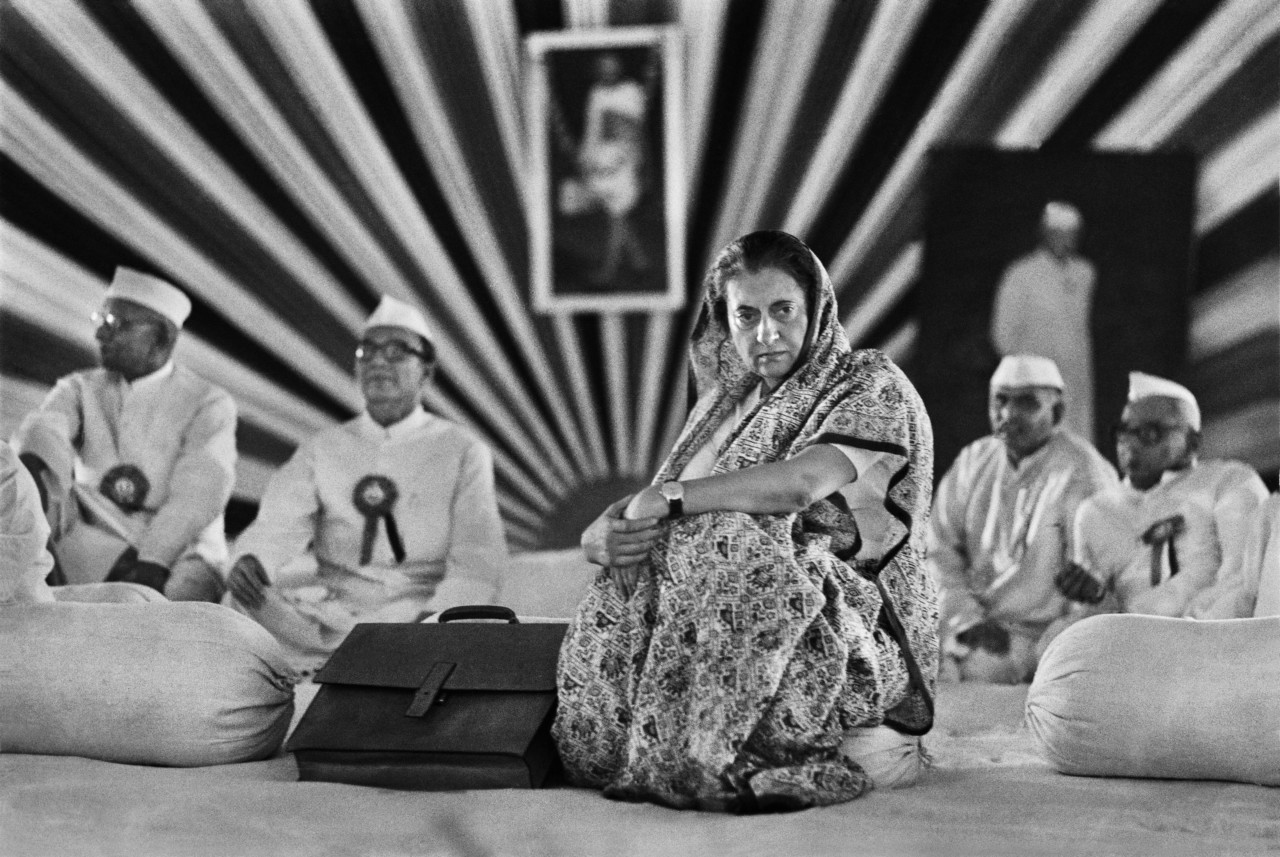

“To be liberated, a woman must feel free to be herself, not in rivalry to man but in the context of her own capacity and her personality”, Mrs. Gandhi once stated. A belief that the prime minister lived by, and that Rai was acutely aware of. In his early shots of her dating between 1966 – 67, Mrs. Gandhi sits apart from the busy cluster of male politicians, who unaware of the camera, are the antithesis of the leader. Gandhi, instead, faces the camera with a direct, unwavering gaze, asserting her reassuring authority. As Rai pinpoints, “Even though Mrs. Gandhi is standing with them, she is looking beyond, her eyes are on the future.”

"To be liberated, a woman must feel free to be herself, not in rivalry to man but in the context of her own capacity and her personality"

- Indira Gandhi

In a portrait of Mrs. Gandhi standing with Pakistani President Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, about to sign the Simla agreement, Rai captures the Indian prime minister a few steps ahead of her companion. “We used to joke back in the day about this picture and say that it showed ‘Mr. and Mrs. Bhutto’” Rai says, before adding “Somebody put us straight on that account when he said ‘Mr. and Mrs. Ghandi’.”

In 1972, Gandhi experienced troubles. A political opponent had accused her successful campaign in the 1971 elections of grave malpractice. Under this dark cloud, Gandhi started to display increasingly autocratic tendencies, that would act as a portent for her following years in office.

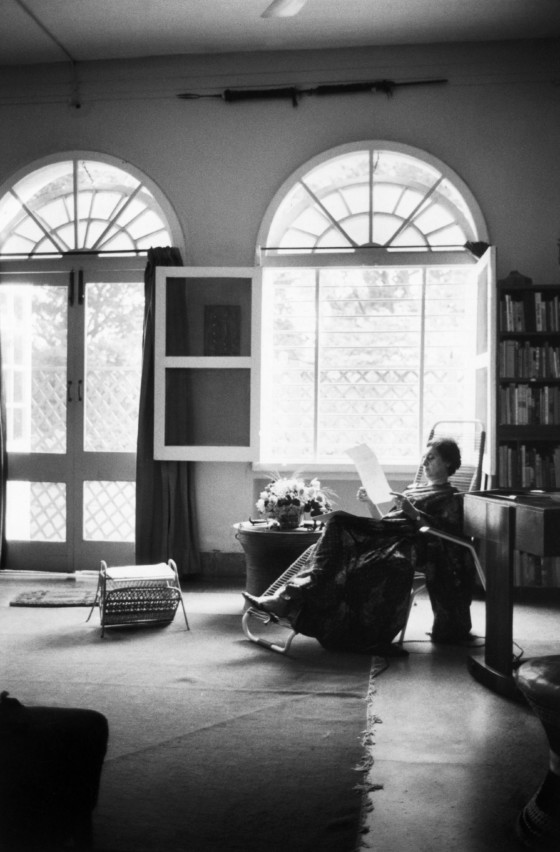

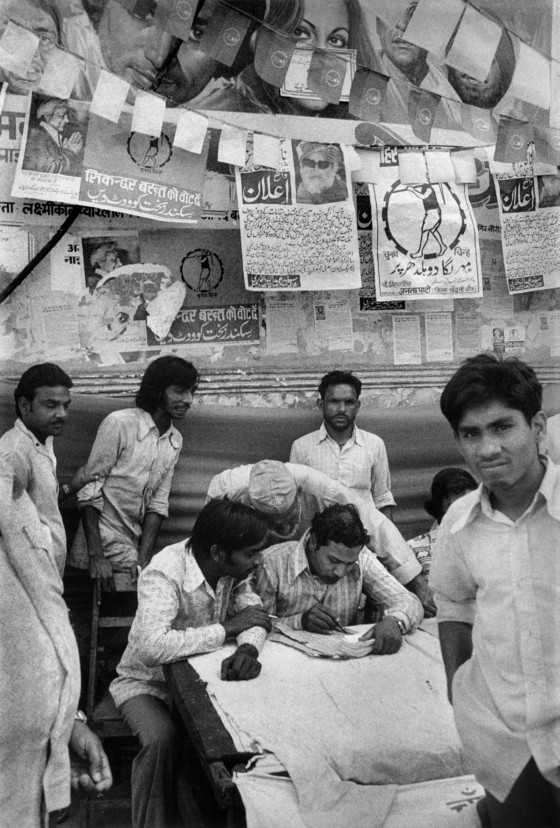

Marilyn Silverstone – an active Magnum photographer in the 1960s and 70s – who spent time with the Prime Minister and followed her closely throughout her political life, would directly experience this turn of events. Silverstone’s earliest photographs of Gandhi show her as a young, determined woman at her desk as ‘President of the Indian Congress Committee’; rallying support above vast crowds and conversely, quietly reading in a sunlit chair in her own home. Yet the relationship would turn sour when Silverstone’s partner, Frank Moraes – a right-wing newspaper editor – angered Gandhi in his Myth and Reality column for the Indian Express, with his vocal criticism of her political decisions. With tensions mounting, the couple were forced to flee in 1973.

In 1975, Gandhi declared ‘The Emergency’, a 21-month period of chaos whereby India was placed under martial law. When the court eventually found the prime minister guilty of malpractice, it was expected she would resign and not return to politics for six years. Instead, she suspended citizens’ civil liberties, incarcerated dissidents and curtailed freedom of the press. The move proved a disaster. Gandhi had strayed from her democratic vision, largely rumored to be under the influence of her son, Sanjay.

Rai wrote: “political analysts, politicians, and commentators have their own understanding of this complex and chaotic time, but being an instinctive person, I look at it from a more human angle. Mrs. Gandhi had grown up with a sense of security and had seen the power her father wielded, the respect he commanded, and she reflected this in her own way”.

His photographs quietly told of her recklessness as a political leader at a time when overt criticism could have landed Rai in danger, but also of her vulnerabilities as a mother. “It has been a decade since Pandit Nehru’s death in 1964, Mrs. Gandhi was now insecure and at a loss. When Sanjay rose to the occasion, she suddenly found a man in the family she could rely on.”

"Political analysts, politicians, and commentators have their own understanding of this complex and chaotic time, but being an instinctive person, I look at it from a more human angle. "

- Raghu Rai

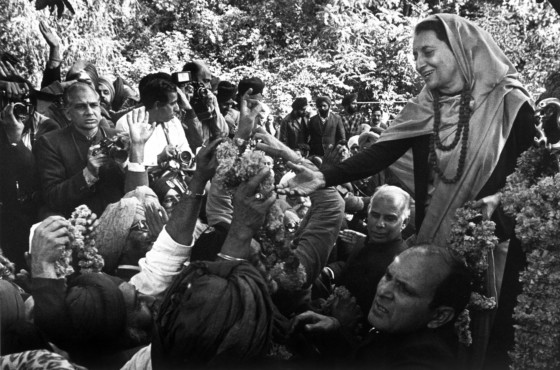

Over the next few years, the ‘The Emergency’ was lifted and India returned to democracy. However, the ruling Janata party had failed to act on the country’s widespread poverty crisis, and Gandhi saw her opportunity. Raghu Rai’s 1980 election portrait shows her hands clasped in prayer, thankful for her return to office. A wide smile replacing her austere expression of earlier years.

Her eventual downfall would come when Sikh separatists seeking an autonomous state overtook the Golden Temple of Punjab. Gandhi sent Indian Military to quell the uprising, but instead a massacre ensued, with hundreds of Sikhs dying. Afterward, she knew her assassination was imminent and decided to meet it with dignity.

Over nearly four decades, Indira Gandhi’s political career was documented through the lenses of Magnum photographers, with her defeats and victories magnified in one long timeline. Yet, ultimately, the aim of both Raghu Rai and Marilyn Silverstone was to capture the woman behind the myth, to unmask her flaws as well as virtues. As Rai wrote, “When I started doing this, I realized that if someone in the future didn’t know who she was, and what a strong personality she was, what a tough leader she proved to be, perhaps they would realize that by looking at these photographs. I began to ask myself, does this picture stand the test of time by itself, for itself? These pictures of her capture some of her essence.”