Smethwick: A Town in England

A multi-authored perspective on the British town of Smethwick, which voted overwhelmingly to leave the European Union in the 2016 referendum

Magnum Photographers

Smethwick is a diverse and traditionally working class town in the Midlands region of the United Kingdom, which voted overwhelmingly to leave the European Union in the 2016 referendum. Following the referendum result, Magnum’s Mark Power captured the architecture of the town, while Diana Markosian documented some of the town’s inhabitants, whose individual stories are told in the photographs’ captions. Hamish Crooks, who grew up in the British town of Smethwick, pens a personal perspective.

This feature is part of Magnum’s ‘Modern States of Britain’, which takes the current political temperature in the United Kingdom following the referendum vote to leave the EU.

“If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Liberal or Labour” – Election slogan used by winning Conservative Party candidate in Smethwick, 1964

“Any normal and fair-minded person would have a perfect right to be concerned if a group of Romanian people suddenly moved in next door.” – Nigel Farage, 2014

We’ve come a long way in 50 years, but the sentiment remains. This racist and xenophobic mistrust of foreigners has been singled out as the main factor in last year’s Brexit vote. But is the narrative that simple? Why did some urban areas with over 50% of residents having recent origins outside of the UK also vote for a policy of exclusion?

Smethwick, in the Black Country (the name is derived from the factory pollution that turned the sky black), part of the greater Birmingham conurbation, is typical of the radical changes to urban Britain’s racial demographic. In the 1950s and 60s, Commonwealth citizens mainly from the Indian sub-continent and the Caribbean with the right to live in the UK, emigrated here to alleviate post-War job shortages particularly in public services such as the National Health Service and transport. Later, law changes led to immigration from the Commonwealth slowing, while immigration from people seeking asylum, students and general workers from all parts of the world alongside economic migrants arriving from east Europe increased due to the freedom of movement enshrined in EU membership. All immigrants do have one thing in common – we are the product of migration, but personal opinions are not solely based on this one shared fact.

During the first influx of Commonwealth immigrants, Smethwick was labelled “the most racist place in Britain” after the notorious sloganeering of the 1964 general election campaign. Malcolm X, invited over by the Indian Workers Association to show solidarity with the Smethwick’s black and Asian workers, made his last speech in Marshall Street before his assassination, stating “I have come because I am disturbed by reports that coloured people in Smethwick are being treated badly.”

In 1984, a Sunday Times Magazine story titled “Black Country Blues: Ghetto Britain”, led the journalist to describe his Sandwell experience as “probably the most depressing story I have ever worked on in my career”.

In its heyday, there were an estimated 90 steel foundries in 5 square miles in the Black County churning out the machinery that fuelled the Industrial Revolution. Punjabi Sikh men filled the post-war employment void, with inevitable “new immigrant” horror stories, such as workers used to warmer climes sheltering from the British cold during their work break in the furnaces, but coming a cropper when the doors were closed. There was undoubted tension with the new arrivals and far more overt racism, but, overtime, it worked. Alun Severn, a friend who grew up in legendary Marshall Street said, immigration today seems to be more of an issue than back then.

Smethwick is representative of the changes experienced in Britain’s working class areas. Once dominated by skilled, industrial scale manual work that slowly decreased through the 1970s, until almost disappearing in the 1980s recession. Once overwhelmingly white and working class, these urban areas, now far more multiracial and multicultural, are not immune to the economic disadvantages of the post-industrial era. In Smethwick today, small engineering firms such as Brooks Saddles are still opertaing, but the foundries have completely gone as have engineering work. For second generation immigrants, the industrial jobs were typically replaced by motor mechanic, TV repairman, taxis and electrician type jobs of the 1970s and 80s – work that paid enough for a decent living at the time – but today replaced by minimum wage, zero hour or gig economy contracts and the same crappy life chances that go with them. Whereas a high percentage of Smethwick residents worked in Smethwick until the 1970s, Birmingham and its service industries is the bigger draw today.

Many of the crumbling 1950s tower blocks and maisonettes that punctuated the skyline from Windmill Lane over to Oldbury and West Bromwich have been demolished to be replaced by small housing estates of modern semi-detached and terraced housing. Smethwick is still predominately made up of Victorian terraced housing, but the demolition of the blocks has changed the landscape dramatically, and for the better. From a commercial perspective, Smethwick’s high streets have not been colonised by the identikit list of big brand companies you commonly find on most UK high streets. There’s a few recognisable chains in the shopping precincts, but most are locally-owned retailers trading in everything from food to clothes to luggage.

I moved to Bearwood, part of Smethwick, in the hot summer of 1976. We were definitely moving up, leaving behind the six floor of a tower block on the sprawling Lea Bank council estate for a house and garden in a seemingly “safer” area with large parks, better schools and less social problems. Indeed, Bearwood was, and still is, viewed as a “respectable” working class area compared to the High Street area. Growing up in 1970s and 1980s Smethwick, there was more optimism about our future than I sense in today’s generation of under 30s. The colour bar experienced by our first generation in the 1960s in some shops, the Bingo Hall and other services had gone to be replaced by our own, “Why would I want to go in there anyway” self-induced bar.

Typical of the UK’s multicultural experience, if different races and cultures are thrown together, though the first generation retain the mistrust of strangers, their children inevitably just get on with life with whoever is around. The racist dogma may still linger and influence certain decisions, but largely, within the groups of working class youths, there’s other pecking orders that transcend race, such as fighting ability or how you can buck the system and prosper. My white British friends liked the same music, played the same games and ate the same food we did. We had acquaintances join far-right groups, but largely the various gangs were multiracial and affiliated more to the area than your racial origin. These groups of youths from various ethnic backgrounds would combine against forthcoming threats, into the loosely affiliated ‘Smethwick posse’. There would be running battles with skinheads from Quinton and beyond, and a feature of growing up then was that I can hardly remember a Saturday pub night that was not punctuated by someone being glassed or having a pool cue wrapped round some unfortunate person’s head. Today, the mindless violence has lessened, though economic and street crime is still a big issue for Smethwick residents.

It’s also more apparent that there’s a more diverse range of communities in the area than previously. The majority of immigrants in the 1950s and 60s came from India, Pakistan and the Caribbean are now being joined by recent arrivals from West and East Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and Eastern Europe. It’s relatively cheap to live and rent in Smethwick, so new arrivals often start their lives here. So you now have Eritrean church services in Victoria Park, East European supermarkets on Cape Hill or a Ghanaian wedding at the local community centre, alongside the more established Sikh temples and African Caribbean churches.

Ironically, the arrival of new immigrants often reinfuses that buffer zone between the working class and the new immigrants, with the previous immigrants “moving up” the social strata, and sometimes sharing in the mistrust of the newcomer as they encountered.

One recurring theme that struck me was how much more British third and fourth generation immigrants feel compared to the second generation. They genuinely feel this is their country and, like it or not, the country needs to connect with them. The more recent immigrants are generally more optimistic, much like our parents who arrived in the 1950s and 60s. The previous, more-inclusive, immigration policy fed our parents’ imaginations to “get on their bikes” and look for work in the ‘Mother Country’ and despite the undoubted problems faced with the in-your-face racism experienced in most aspects of public life, they knew they were sacrificing their own careers for the next generation.

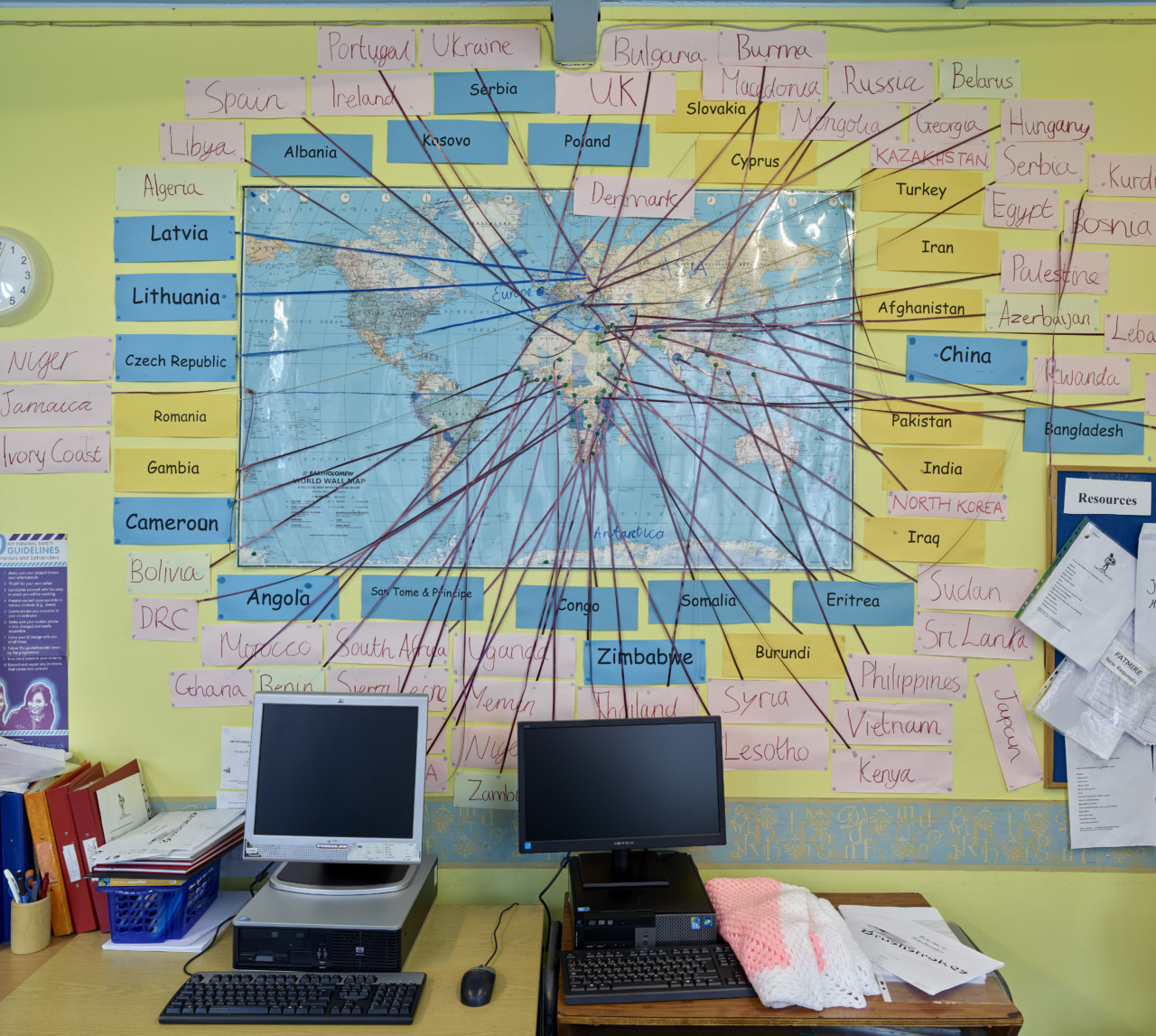

The optimism of the new immigrants is helped by the improved support network for new arrivals, such as Brushstrokes in Smethwick, which helps asylum seekers settle into the area. Our parents arrived without any basic information on living in the UK, while the host population, more often in white working class areas, didn’t know we were coming and there was no internet to Google “typical customs of Sikh men”. We just arrived with a few suitcases looking for work and hoped for the best. Just like today’s immigrants, many of the first arrivals are single men, sent ahead with the aim of returning home after saving enough money for a better life. In reality, unemployment and lack of educational opportunity back home meant they were paving the way for the rest of the family to come to the UK. I’ve recently heard people talk of immigrant men “hanging around on street corners” – identical to comments on the 1950s immigrants – which then often leads to suspicion, but similar to our experience, many men hang around as they’re sharing rooms with other first generation immigrants and so loitering outside is the only place to go that has no cost.

First and second generation immigrants often have closer ties to their ancestral home country, but this fades as new generations establish greater roots in their new home. Once you’re future is rooted in the UK, it’s no surprise that the next generation’s optimism is tempered by the continued inequality in opportunity that their parents reluctantly accepted. It’s the same pessimism for the future experienced by white working youth. This can be reflected in the feeling of alienation to the rest of the nation and which sees a few white youth joining nationalistic groups and a few Muslim (and non-Muslim) youth of immigrant origin heading for Syria or listen to Islamist preachers spouting hatred – they are seeking their own path on their own terms. Most of us just moan and get on with life, but like youth everywhere, there’s no prescribed model to personal success.

I, like many of my generation, failed the Norman Tebbit-test completely – I didn’t support the England football, cricket or rugby teams, though I can be more objective of their performances today. I’d have long debates in my head on how I would reject a call-up for the England rugby or football teams, but thankfully, my ability meant the call never came. I was always a Smethwick boy, but I didn’t feel British till 1992 as there was always a lingering feeling growing up in a background of the National Front, racially-aggravated riots and institutionally racist public services that we would “go home” involuntary. Jamaica was great for holidays, but unfortunately did not feel like home – everyone there called me “English”, and besides, I was mixed race, so where was home? I can still pinpoint the moment I truly felt British – Linford Christie winning the 100m at the Barcelona Olympics, this most Jamaican of men in our eyes, ran around the track with the British flag at a time when flying it was still viewed as nationalistic, i.e. white. We’d grown up hearing songs like, “There ain’t no black in the Union Jack”, but what Linford’s gesture said was, “I’m British – deal with it” and I completely bought into that. From the highs of winning gold to the lows of the next day as the popular right-wing press could not bring themselves to celebrate a British winner of the Olympics’ blue-riband event and instead shamefully focused on “Linford’s lunchbox” jokes.

Speaking to Smethwick friends from all backgrounds, you hear support for Brexit from a diverse range of perspectives, belying the populist view we hear quoted repeatedly that Leavers were just dumb. These range from the “Fortress Europe” argument that has resulted in the inability for people of Commonwealth origin to move to or even visit to the UK as preference is given to EU citizens, to the British Asian shopkeepers who don’t like the Polish shop now taking business from them, to the neo-Marxist argument about the Thatcherite capitalist structure enshrined in the EU finance policies, the strain of public services and the welfare system in times of austerity and the marginalisation of the working class. You do still hear the “too many of them, taking our jobs and over-using public services” sentiments, but there’s far more nuances to Leave than the “too dumb to vote” suggestions we heard in the aftermath. Underlying it all, you sense this was a revolt against a self-serving political elite, from all political perspectives, ignoring issues affecting the daily life of the average working class person – low wages, housing shortages, educational disadvantage and health problems. No one wants to advertise how they voted in the referendum as support for Brexit can be seen as support for an unshared viewpoint – my straw poll revealed a 50/50 split between Remain and Leave for Smethwick.

The basic fact is why would anyone vote for the status quo if the status quo is not working for you? It seems the Remain camp hoped everyone would do as the popular cartoon states and “Keep Calm And Carry On” and vote blindly like sheep.

There are differences of opinion between the generations of immigrants and a sure sign of integration is when the second and third generation immigrants vote on economic policies affecting them personally, rather than sticking to single issues affecting minority groups specifically. Generally, the most important issue in a UK general election is the economy, not foreign affairs – remember how Labour won the 2005 election in despite the majority of people abhorring our involvement in the Iraq War? Why? Because we trusted Labour with the economy.

What seemed to define the Brexit vote was austerity. Before the crash, the Conservative victory and subsequent cutbacks, there was always a little tension between different waves of immigrants and you would occasionally hear some misguided African Caribbean or Asian friend argue that there’s “too many East Europeans here”. But I felt the austerity measures polarised opinions as the need to battle for a smaller share of resources tightened. Throw in a once-in-a-lifetime referendum where every vote actually counts, and we have another factor in Brexit. When only one-in-four of eligible voters actively voted for the current government in the least General Election, is it any surprise they were not backed in a straight two-way fight?

None of the second or third generation of immigrants I spoke with thinks Nigel Farage’ xenophobic rhetoric would deliver a perfectly harmonious society based on social justice. But Labour, the supposed social justice champions, who in the 70s and 80s were far more connected to their constituents through life and work, today speak like technocratic career politicians and have less connection to the people they seek to represent. Politicians speak of “engaging” and “understanding” these “communities”. Even the use of the word “community” is loaded – more often based on race or religion (e.g. the Muslim community) as if there is no diversity of opinion within these groupings. Now we hear the “white working class” is a community too.

If a politician or public servant has to begin to understand a community you are paid to represent, with all the tokenism that suggests, it’s not going to work. And why are public servants not engaged already, after all, we are all tax-payers? The revelation emerged during Ed Miliband’s failed election campaign that not one of his election team of politicians and political workers knew a single person on minimum wage with whom Ed could meet to “earnestly” listen to their voice in a televised meeting. This was symptomatic of where politics is today and why many people are turned off or turn to anti-establishment groups, while the winners in society increasingly refer to the losers “learned helplessness” as if working class life is just another episode of The Jeremy Kyle Show.

So what does the future hold for Smethwick in post-Brexit Britain? The more pessimistic view sees an increasing marginalisation of the working classes whereby the void created by inaction sends many into the waiting arms of the far right, who repeatedly piggy-back off other popular movements, but with far more divisive and dangerous intentions.

The optimistic side is that youth always find ways, just as we did in Smethwick, to traverse the macro issues affecting their lives and create relationships with any other like-minded people close to them. Or at least live side-by-side as we see in the American model of immigrants – you are always American, be it Italian, African, Irish, Ghanaian, Nigerian, Indian – often separate culturally, but all are American. Brexit, though with negative consequences elsewhere, may actually be the line in the sand to tell our policy makers, that the people we’ve chosen to ignore because they don’t vote, can no longer be brushed aside as “collateral damage” of politics.

This project is a co-comission with The Guardian, featuring in today’s edition of the Guardian Weekend magazine. Read more interviews with people from Smethwick online on The Guardian here.