Alec Soth on Learning From Failure

The photographer reflects on regret, abandoning projects, and learning from mistakes

Magnum Learn‘s second on-demand online course – Alec Soth: Photographic Storytelling – offers unique insight into Soth’s practice and process through more than five hours of exclusive video content featuring in-depth interviews, on-location shoots, practical demonstrations, and deep dives into his best-known photobooks.

Below, to mark the course’s launch, Aaron Schuman speaks frankly with Soth about the importance of learning through experience and in particular about acknowledging and overcoming the mistakes, errors, frustrations and ‘failures’ that inevitably occur along the path of any photographic career. Soth shares specific examples of technical errors with Schuman, as well as reflecting upon the difficulties of letting projects go, the importance of reconciling oneself with the inevitability of making mistakes, and the vibrancy error can bring to work.

You can learn more about the new Magnum Learn course, here, and watch the course trailer at the bottom of this article.

Aaron Schuman: I wanted to have a conversation with you about the process of learning in general, and more specifically one that is centered around overcoming the notion of “failure” within the photographic process. Often there’s a misapprehension that “great photographers” have some sort of “magic touch” when it comes to making pictures. But, as anyone who has seriously engaged with photography knows, it’s a medium that requires the practitioner to make mistakes, employ trial and error, and learn from small, sometimes heartbreaking “failures” along the way. In a sense, these things are essential to the photographic process. How do you work through and overcome the frustrations of “failure” when you’re making new work, and how have you learned to take advantage of those accidents and mistakes when they do inevitably happen?

To start, I think that the biggest and most obvious mistake that many photographers sometimes make when they see a potential photograph is – out of fear, uncertainty, self-consciousness, self-doubt, or otherwise – to not take the picture in the first place; there’s a moment of hesitation, and then the opportunity disappears forever. Do you ever still find yourself in these situations, and if so, how have you learnt to deal with them?

Alec Soth: The good thing about discussing these issues with you right now is that I’ve just returned from a three-week-long photographic road-trip, so a lot of the things that you’re describing are right at the forefront of my mind, being processed as we speak. Also, I was traveling with a twenty-three-year-old photographer, and it’s interesting to think about it through their eyes as well.

For example, at one point during the trip I drove up to a scene that seemed like a potential picture. Then, out of nowhere, a woman on a bike goes by, and she’s absolutely fantastic. But of course, she’s travelling quickly, so I have to do the mental calculations very quickly – is this a person I want to stop and talk to? How will I explain myself? How will she react? It’s almost like my brain is a computer – it has to weigh up the pros and cons of stopping this person and creating all sorts of problems for myself; is it really worth all the trouble?

Anyway, in that instance, I noticed just how fast I made that calculation. BOOM – I was out of the car, and almost immediately in the mode of making things happen. I think that my assistant was shocked by just how fast I pulled the car to the side of the road and made everything happen.

So I’ve definitely learned from experience, yes. Because of course, I’ve gone through that scenario a thousand times in the past – where I’ve seen something but kept driving, and five blocks later thought, “I should have stopped.” I’ve turned around, but inevitably never found the person or the situation as I first saw it.

Furthermore, for me an important part of this calculation is also determining whether each picture I make is connected to a larger personal project; is it just an interesting picture, or is it somehow related to everything else I’m doing? Of course, there’s only so much time to think through what that means, so you also have to learn how to listen very carefully to your own intuition.

"I’ve gone through that scenario a thousand times in the past – where I’ve seen something but kept driving, and five blocks later thought, 'I should have stopped'"

- Alec Soth

Are you better at listening to your own intuition now than you were earlier in your career?

Absolutely. As a photographer, your instincts are getting thrown off all the time, often because you see something that looks just like a picture you’ve seen before, so you stop. That’s where experience really helps – sometimes you realize, “Oh no, I’m just doing this because it looks like a Winogrand” or whoever. But then, sometimes your intuition tells you to go for it anyway; you don’t know exactly how it’s connected to what you’re doing, but you have a sense that there’s something there that’s connected to what you’re generally after.

Also, now when I do miss something, or even when I take a picture and it doesn’t turn out how I wanted, I just let it go. It’s like being a fisherman standing by a stream – the fish just keep going by, and you can’t catch all of them; it’s not worth beating yourself up about that.

So you don’t beat yourself up anymore?

Well… on this last trip there was one situation where I beat myself up. I’d just made one picture, and was going to get some lunch, but on the way I saw this scenario that involved a group of people coming out a of bible-school, and a tree…

“Classic” Soth.

[Laughs] Yeah, I’d just been photographing and thinking a lot about trees, so when I saw this scene it was amazing. I did the calculation – “I’m hungry, it’s lunchtime, but I’m going to jump out of the car anyway” – and started talking to them, setting up my camera, thinking about how this particular tree connected to the trees I’d just been photographing. I started making some pictures, and kept pushing different strategies to get the people and the tree together in some way, but it wasn’t really working. One boy was holding a stack of Christian literature, and I tried to work that into it too.

Anyway, eventually I stopped shooting, but as I drove away, I realized that the picture I’d been looking for wasn’t really about the people; it was something to do with the Christian literature and the tree. And I was like, “Ugh.” I beat myself up pretty hard about that; the fact that I didn’t realize I could have simplified the picture – it was right there, I had the permission, the opportunity, everything was perfectly set up for me to get what I wanted, but my head just couldn’t make the connection at the moment.

That’s the kind of thing I beat myself up about these days.

"All these things that you do and see, and all of the mistakes you make, they have a vibrancy to them"

- Alec Soth

Another type of “failure” that occurs within photography, even when a photograph is taken, is the technical error – the exposure, focus, composition, or whatever is off – but you only discover it after the fact. Does this still happen to you?

Yes. It’s always happened, it continues to happen, and it just drives me crazy.

One way I try to counteract that is to do more than I need to do. There’s a common phrase that a lot of photographers use – “Can I do just one more?” – which is really about covering your ass on a technical front; bracketing, changing the composition ever so slightly, or whatever. In my own case, my technical struggles generally revolve around focus, so when I “do one more” I’m often trying to battle that by stopping down, or using different depths of field, and all that kind of stuff. Composition sometimes is an issue – I look through the camera and something just feels clunky; so I keep trying different things. And then you get the film back, and so often the picture still just doesn’t work.

Of course, one big solution to all of this is to shoot digitally, and then you can check your focus and composition on the spot. But the problem then is a sort of technical overcorrection. You are so focused on technical issues that you’re not focusing on engaging with the subject matter, which creates an image that is technically perfect, but dead. That said, at many points in my career I’ve been seduced by digital photography and its ability to resolve technical problems, and it’s still something I sometimes use, and find comfort in, especially when I’m shooting a commission or job rather than a personal project.

"Sometimes imperfections make something even better - which is one of the reasons why I still enjoy shooting on film"

- Alec Soth

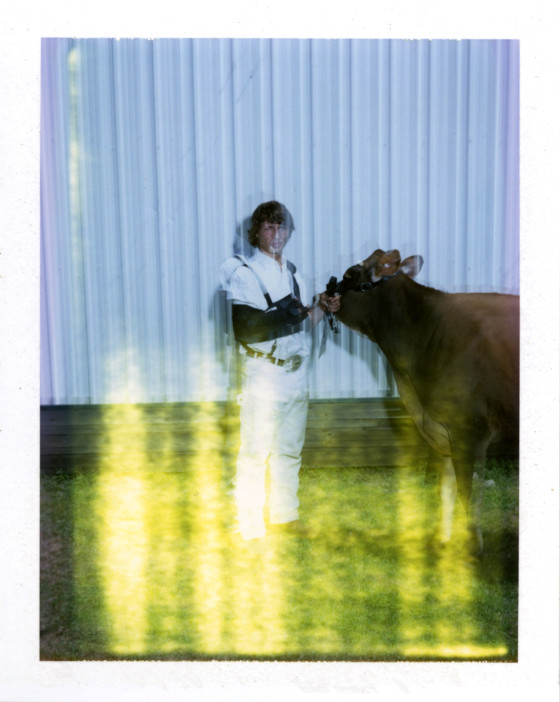

Have you encountered instances in which a technical mistake has improved upon your initial intentions?

Oh yeah, millions – sometimes imperfections make something even better – which is one of the reasons why I still enjoy shooting on film.

In relation to technical failure: just yesterday my son and I went to a baseball game, and I was thinking a lot about how a batting average of .400 – a success rate of forty-percent – is considered amazing in that context. A lot of the failure that occurs when you’re batting in baseball is due to small technical errors; you are leaning in too much, there’s a slight flaw in your swing, your timing is off… I think that if we looked at the percentages in photography then the success rate would be really low: the point at which you’re doing everything technically right, and then you’re also presented with perfect subject matter and situation, and all of the elements (weather, light, etc.) come together – that’s a pretty magical thing. One of the main lessons that experience has taught me is that something like that is exceptionally rare.

"The point at which you’re doing everything technically right, and then you’re also presented with perfect subject matter and situation, and all of the elements (weather, light, etc.) come together – that’s a pretty magical thing"

- Alec Soth

When my son first started playing baseball, he would beat himself up every time he didn’t get on base; he wanted to walk off the field and cry. But then he learnt that he couldn’t expect to get on base every time. If every time you go out to take pictures you beat yourself up for not creating a masterpiece, it’s going to become a serious problem.

That’s not to say that I don’t feel frustration – I feel it all the time. It’s very rare that making photographs is wholly satisfying; that’s part of the job. You can’t always hit a home run and jog around the bases feeling great about yourself. It’s an amazing feeling when that does happen, and I suppose that’s why you keep trying.

What about when, in the moment, you really did feel like you hit a home run – you think you’ve made a great picture – but then a week or two down the line, or even a few months later, you realize that it was actually a “foul ball”; that it wasn’t as great as you’d first thought?

[Huge sigh.] Yeah, you’re kind of hitting me at a raw moment right now! [Laughs] The film from this recent trip is being sent off to a lab today, and I won’t see what I’ve got for another five days. So, I’m at that point where I think there are several really great pictures in there, but I’m still nervous about it all. I know that some of them won’t be as good as I think they are right now. And I also know for a fact that there will be at least one photo that I’ll continue to tell myself is a great picture for a certain period of time, until I finally learn that it’s not. Really, it all comes down to patience.

If fact, the whole practice of photography requires patience, as well as the ability to let go. Something that I talk about a lot when it comes to editing, but which I guess applies all the time, is to try and relax into the process, which often means not holding on too hard to those pictures that you think are amazing; let them go and keep moving forward. Also, by relaxing you can occasionally discover something special in the photographs you didn’t initially rate, that you felt so-so about – you can come to see something interesting or important in them in relation to the whole project.

Has your capability to relax grown over time?

Over the years, I’ve learned to not be so uptight. Recently, while travelling with this younger photographer, I noticed the amount of anxiety they would sometimes feel about whether or not they should take a picture, or whether or not they were good enough, or whether or not that imaginary audience that we all carry around with us in the back of our minds would like the photograph that they were making. At the same time, you can’t be so laissez-faire that you don’t give a shit – then it’s time to retire. So, it’s a balancing act.

I know those feelings so well, but I feel them less and less these days, and I guess that I’ve learned through experience to just relax into it. That’s where experience and patience pay off; there’s no getting around it. I remember that when I was younger, I found this kind of advice incredibly frustrating. At that stage you’re like, “I don’t want to be patient!”

"I’m totally for photographers traveling to the ends of the earth to find their subject – do whatever you have to do – but just be authentic and honest with yourself about how you're responding, to both the experience and to the work that you’re making there"

- Alec Soth

To return to your baseball analogy, I also wanted to talk about playing “home” versus “away”. In the past, you’ve alluded to the struggles you sometimes face when working too closely to home, but also to the difficulties of working in countries and cultures that are not your own.

An important thing to say about my process nowadays is that I don’t photograph all the time. I’ve come to realize that I can’t live my life like that; if I’m on a walk with my child or whatever, I don’t want to be constantly racing off because I see something that could be a picture. My struggles in terms of working closer to home have mostly to do with everyday domestic life creeping into my time and effecting my quality of attention, on top of the fact that I need to be even more focused because I’m in a place is almost too familiar. Now, when I’m not out specifically working, I barely register the things around me as photographs.

But when I am out photographing, I’m in full work-mode – I punch in, tune in one-hundred percent, and am prepared for anything. And when I’m travelling, I can be totally focused because there aren’t any distractions; I don’t have to feed the dogs, run errands, or whatever. That quality of focus, combined with the fact that everything I’m seeing is generally unfamiliar, provides a lot of potential for good work.

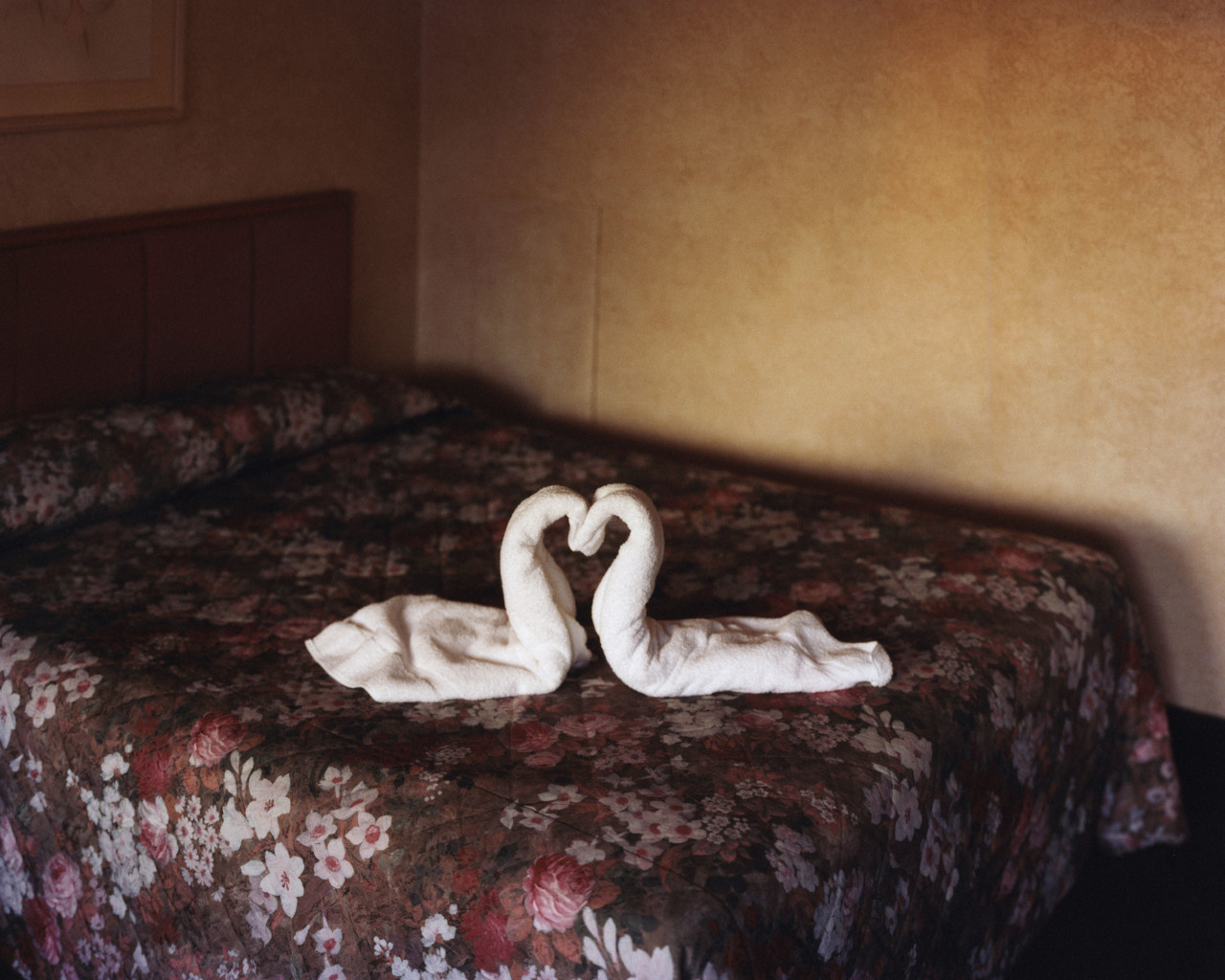

Regarding the “away” game – making work in a foreign country or wherever – I think that every photographer should try lots of different kinds of photography, and then listen deep down to what feels right; what’s really resonating within them. In my own case, I loved the work of Larry Sultan so much that I wanted to be just like him, so I tried to make work like his – for a while I made family-type pictures at home – but eventually I realized that it all felt a bit forced and fake. The same thing happened when I tried to be a shoot-from-the-hip, every-day kind of photographer like Winogrand. The same thing sometimes happens when I work in a different country, and don’t feel a connection to the place. And the same thing has happened when I’ve been working on certain jobs as well – suddenly I’m in the middle of shooting a fashion campaign, and I just feel fraudulent.

But there are also times when I’ve experimented far away from home, or outside of my wheelhouse, and I’ve learned a lot of lessons from those experiences, which then get incorporated into my practice. I guess it all comes down to being honest with oneself. I’m totally for photographers traveling to the ends of the earth to find their subject – do whatever you have to do – but just be authentic and honest with yourself about how you’re responding, to both the experience and to the work that you’re making there.

I guess there’s a constant battle going on inside of everyone – between who we think we want to be, and who we really are. Maybe it’s a matter of finding a middle ground. Of course, it’s important to be honest and true to oneself, but it’s also important to have ambition, inspiration, and to be open to new experiences and changes. When did you first tune into yourself in that way, and how did you first discover your own authenticity, whilst also continuing to strive to better yourself and your practice?

We all have that inner voice. I remember when I was starting out, it was the early days of Photoshop, and I made these heavily manipulated pictures. I was having fun experimenting with the process. But there was this thing – looking at them made me slightly nauseous. They just felt wrong to me.

Even last month, I abandoned a project that I’d been working on for more than half a year. I was looking at the pictures, and they weren’t making me sick or anything, but when I really listened to that inner voice I realized that I just didn’t feel thoroughly invested in that work. Somewhere deep down, I knew that I was faking it.

I guess it’s kind of like when you’re looking for a romantic partner. You go on a first date, and you have to think to yourself, “Do I actually connect with this person, or are they just really attractive? Could I really fall in love with them?” At some point, you have to let your initial excitement settle down, and then listen to that inner voice to discover how you honestly feel. Then, of course, you also have to contend with other people’s opinions – “Oh, you should marry that person; they’re amazing!” – and you’re still thinking to yourself, “Really? I don’t know.” We all have to do this in different parts of our lives: trying to quiete things down. It’s one of the reasons that I sometimes try to get away from other people’s opinions– so that I can be more real with myself about what I’m actually feeling.

I’d like to dig a bit deeper into the idea of abandoning a project, which is a common but almost unspoken of experience for photographers. It’s a very difficult decision to make, and a hard lesson to learn. When you recently experienced this, how did you get out of that hole, both emotionally and creatively?

It’s really, really hard. But one thing that photography has going for it, unlike a lot of other art forms, is the fact that if I abandon a project it’s not total destruction. At least the pictures are still pictures, they can sit in my archive, and maybe down the road they’ll have a life in something else. Even though the project didn’t come to fruition, I know that I still have good individual pictures from that work, and that’s somehow comforting to me. So that helps on the emotional side. The main thing is understanding that everything leads me to something else; it’s all just part of the process.

But it sucks; for sure. I begin most projects with real seriousness – I think of them as multi-year, large-scale commitments and give them all of my attention. It’s like when you’re in college, working on your thesis project, and it feels like your whole life is riding on it. I genuinely treat every project with that amount of seriousness. Perhaps that’s one thing that hasn’t changed for me over the years – my whole identity is still wrapped up in each project that I start. So cutting the cord on something is quite challenging, and incredibly painful. But over time I’ve come to realize that this is a necessary part of an ongoing process.

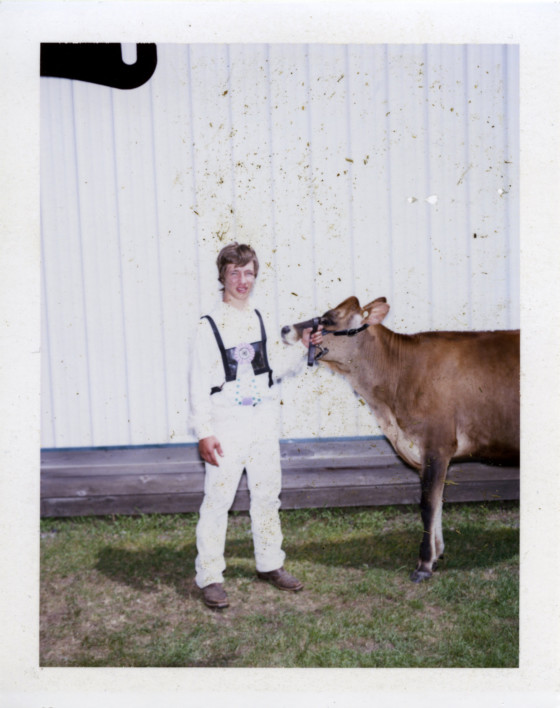

In relation to that, I’d like to bring up your body of work, Looking For Love 1996. My understanding is that you originally shot those pictures in 1996, when you were just beginning to pursue photography, but the project didn’t actually get realized until more than fifteen years later, as a book in 2012.

Like most photographers I tried lots of different ways of working when I was starting out. One of those was using black-and-white film and a flash while shooting in bars. I had my first exhibition around that same time and called it, “At the Bar” – I’d made all the pictures in local bars, and even tried to make the gallery look kind of like a bar, which sounds ridiculous now, but that’s how it happened. Anyway, once the show was over, I thought to myself, “That was a good experience, but it’s not really who I am – I’m not a guy who’s going to be making black-and-white pictures with a flash in bars for the rest of my life.” I moved onto the next thing.

Then, many years later, someone enquired about those photographs. I starting going through my archive and realized that those pictures had been made alongside lots of other photographs that I’d been making around the same time, which had nothing to do with bars or using flash, but did share a certain kind of outlook or perspective. In retrospect, by looking at all of the pictures from that time with fresh eyes, as well as with the editorial sophistication that I’d accrued over the years – and not limiting the work to the original “At the Bar” concept anymore – I could see new possibilities.

So over time, some mistakes and failures can even led to new possibilities.

For sure. And those pictures have a certain energy that’s hard for me to achieve now, specifically because of the naivety and “mistakes” they contain, and because of the period in my life during which they were made. That’s something that younger photographers really do have going for them. Yes, you have to go through all of these struggles, mistakes are made, projects fail or fall flat, you’re often filled with heartbreak or frustration, even more so when you’re told you have to be patient, and so on; but there’s also an energy that’s created because of all of that.

All these things that you do and see, and all of the mistakes you make, they have a vibrancy to them. In terms of Looking For Love, there’s no way I could have seen or understood that back then. But I totally get it now, nearly twenty-five years later, and see how it all makes sense in relation to the rest of my work. And in a sense, even in the face of any mistakes or perceived “failures” I might encounter today, that’s ultimately what still encourages me to just jump out of the car and take a swing at it; it’s what makes it so exciting – it’s what still gives me hope.