On Ambiguity

Stuart Franklin meditates on the role of caption and context in our reading of photographs

Ambiguity in photography begins with confusion over who or what is the photographer, the picture-maker. “I’m a photographer,” I might say. Actually, it’s the camera that is taking the picture, and processing the image data. I am guiding the lens to face the subject, putting the subject at ease, making some adjustments, steadying the machine, making decisions about when the picture should be taken, what should be framed, and how the picture space should be organized.

Principally, I’m a pointer and arranger of content. The camera does the rest. This ontological crisis is something rarely, if ever, addressed. Photography is entirely different from painting or drawing where the mark-making, all of it, is governed by the artist who has a zillion choices to make regarding expression.

Maybe it’s felt that the discussion is inconsequential. It’s not. It faces us the moment we open the door on the question of photography and ambiguity. Any discussion about describing the content or context of the photograph must begin with the magic —that we only partly govern —behind the image itself.

“I think photographs should have no caption, just location and date,” Henri Cartier-Bresson famously commented to an interviewer in the early 1970s. He wasn’t the first photographer to ration knowledge, nor was he the most extreme (I’ll come to that), but since Cartier-Bresson’s axiomatic declaration the photographic community has been split, or at least conflicted.

It would be easy to argue that the image/text issue divides across the faultline that some feel has opened up between art and photojournalism. The Western easel painting tradition, which led to images being hung in “white cube” galleries traditionally favored scant textual distraction around the picture.

Newspapers and magazines differ in approach. Photographers are required to supply not just the names of people in the picture, but their ages, and much more besides. So photographers who come from a painting tradition, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Alec Soth, William Eggleston and Saul Leiter are comfortable with scant detail. Then, so are photographers who don’t come from a painting tradition, such as Josef Koudelka and Richard Misrach, whose 1979 photobook is utterly devoid of text.

Misrach explained how he methodically removed all the text from the photobook’s interior, “the introduction, the essay, the title, image captions, the author’s name, even the page numbers.” I have the book at home and it’s surprising what you can stuff onto a spine—the only place where text appears.

The art/photojournalism split is not quite the point here. Photojournalists differ markedly in the way they offer up detailed textual information, especially when it comes to publishing books. Leonard Freed used to say that ambiguity was one of the great strengths of photography; Everything else, he insisted, was propaganda.

By contrast, the photographer and critic Martha Rosler took Susan Meiselas to task —in a manner derivative of Walter Benjamin’s 1934 attack on visual poetry —for omitting, in her Nicaragua book (1979), “all mention of political convictions and their possibility.” Either way, text alongside pictures, in and of itself, is no guarantee of clarification and many texts muddy matters further.

"I won’t give explanations. My photographs are there; I do not comment."

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

“All photographs are ambiguous,” a state, John Berger argued, that’s fuelled by discontinuity. We never know the history of the moment in a single photograph, nor the outcome. But is knowing more than the photographer or artist has decided to reveal, desirable?

In the 1960s there was a reaction against biography-based, or as Foucault put it “man-and-his-work” criticism with Roland Barthes’ 1967 essay, “Death of the Author”. Van Gogh’s painting, seen through an obsession with the artist’s “madness”, was Barthes’ bête noire: he wanted the work to be appreciated for its own sake.

Barthes may have drawn his ideas from the poet Mallarmé, who wrote that “the pure work implies the disappearance of the poet-speaker.” Henri Cartier-Bresson, an avid reader of Mallarmé, seems to have taken a tight-lipped approach to adding context. In a 1979 interview with Alain Desvergnes, he insisted on the autonomy of his work: “I won’t give explanations. My photographs are there; I do not comment.”

Everything changes. The poststructuralists’ intervention hasn’t done much to brook public curiosity about the author, evidenced by art critics attempting to draw us to the Tate Modern’s current Modigliani retrospective with tales of his short lothario lifestyle in Paris. Nothing, incidentally, was mentioned of his struggle to work during the First World War blackouts in Paris.

Let’s go back to ambiguity and John Berger before trying to work out whether more knowledge about images —from a viewer’s perspective —is desirable. In re-examining Berger’s assertion about ambiguity it turns out that discontinuity is only one of a variety of facets of the complex object we’re trying to examine; there is ambiguity enhanced by factual omission, by certain kinds of illusion, by psychological or emotional messaging, by reflection, and by what can best be summed up as visual poetry.

"All photographs are ambiguous."

- John Berger

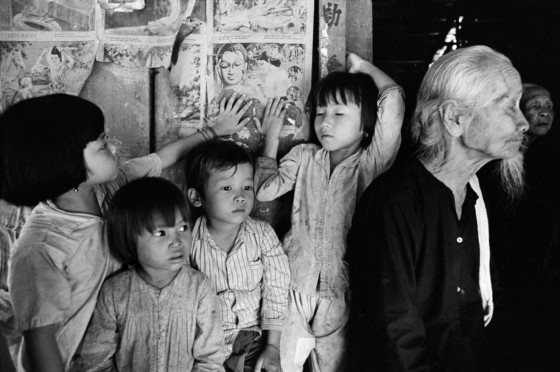

First off, ambiguity as discontinuity is exemplified by Elliott Erwitt’s photograph of a registry office in Siberia in 1967. Why is that man on the left of the picture smiling? What has just been said or witnessed? Consider also the unexplained moment that Krass Clement captured in Paris, of a man seated in what looks like a train station, head bent down beside a bouquet of flowers. Is he asleep or broken-hearted, or both? There’s no caption, no location, no date, and no page number.

Ambiguity is enhanced by factual omission when a photograph that seems to be describing one fact, is actually representative of another. On January 18 2005, the late Chris Hondros photographed a five-year-old girl crouched down in Tal Afar, Iraq, screaming and, seemingly, bleeding profusely. She’s not. The blood’s from her parents who had just been killed by US troops. The picture shows the child lit by a torch, and to her left, the legs of a standing soldier.

On September 11 2001, Steve McCurry photographed a US flag flying at Ground Zero shortly after the Twin Towers collapsed. The impression the photograph gives is that the flag is a miraculous survivor of the devastation —a symbol reinforcing national resolve. But the flag was removed by firefighters from a charter boat on the Hudson River and hoisted amid the rubble a little while before the photograph was taken.

Forget, for a moment, the metaphorical death of the author. What about the actual death of the subject? Today when photographs of the dead and dying playback to virtually every town and village globally, it would seem respectful to accompany photographs with as much context as possible. The German newspaper Der Tagesspiegel’s decision to print over 46 pages, the names, ages and causes of death of 33,293 refugees and migrants trying to reach Europe since 1993 is a commendable move, and we’ll hopefully see more of this kind of sensitive attention to detail.

"Ambiguity is enhanced by factual omission when a photograph that seems to be describing one fact, is actually representative of another. "

- Stuart Franklin

Factual omission then, also includes the decontextualizing of news images. In November 1969, the Cleveland newspaper, The Plain Dealer, published Ron Haeberle’s famous photograph of the My Lai massacre in Vietnam on the front page. Underneath, the caption read: “A clump of bodies on a road in South Vietnam.” Fifty years on, clipped captions and emblematic pictures of the nameless dead have a tendency, more and more, to ‘Other’ the subject, not bring him/her or the affected people closer, but to push them further away. The onus is on us to balance the needs of public interest reporting with sensitive attention to detail and true context in relaying the facts, while at the same time—and this is what has really changed—recognizing the universality of today’s news images.

Playing with illusory visual codes in order to introduce ambiguity into the reading of the image is something we see in a variety of genres. Consider René Magritte’s confusing painting La Condition Humaine (1933) where the canvas morphs onto the landscape, or Edward Weston’s Cabbage Leaf (1931) where the picture oscillates between two or more interpretations: folded fabric and a cabbage leaf. In Jonas Bendiksen‘s 2005 photograph by the Black Sea in Abkhazia, the viewer is challenged to question whether the bear is real or fake.

Metaphysical painting from Rogier van der Weyden’s The Vision of the Magi (1445-48) to Francisco Goya’s El Vuelo de Brujas (1798) is the referent for Carl de Keyser’s photograph of a passion play from his Bible Land series (1990). Ambiguity is introduced both from the suspended belief in our ability to float in mid-air and some background recognition of the Bible story, which of course is culturally specific.

Ambiguity derived from emotional or psychological messaging is all about nuance. Psychological messaging is ubiquitously found in the world of advertising, in creating what René Girard described as “mimetic desire”, whereby we yearn to be like the people in possession of an object of desire.

Emotional messaging is best described by examining portraits that seem to betray an underlying relationship between subject and author. Édouard Manet’s painting of Berthe Morisot holding a bouquet of violets (1872) and Robert Mapplethorpe’s photograph of Patti Smith taken for her debut studio album (1975) both seem to shimmer with an intangible tension.

"Ambiguity derived from emotional or psychological messaging is all about nuance. "

- Stuart Franklin

Intradisciplinary hat-doffing is where photographers (in the following examples) reflect on work by other artists; it is a visual form of intertextuality. We see this delivered subtly in De Keyser’s Bible Lands picture. The ambiguity of Jeff Wall’s A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai) (1993) is enhanced for those who don’t know Hokusai’s original oeuvre. Similarly, those viewing Alec Soth’s Fishermen, Wickliffe, Kentucky (2002) might have missed the interview where he describes the photograph “as my ultimate Jeff Wall.” Having read that, I was keen to know whether the picture was a composite made up of several photographs stitched together. Soth answered my question: “I just meant it had the feel of a Jeff Wall image,” there was no compositing.

"I prefer people to look at my pictures and invent their own stories."

- Josef Koudelka

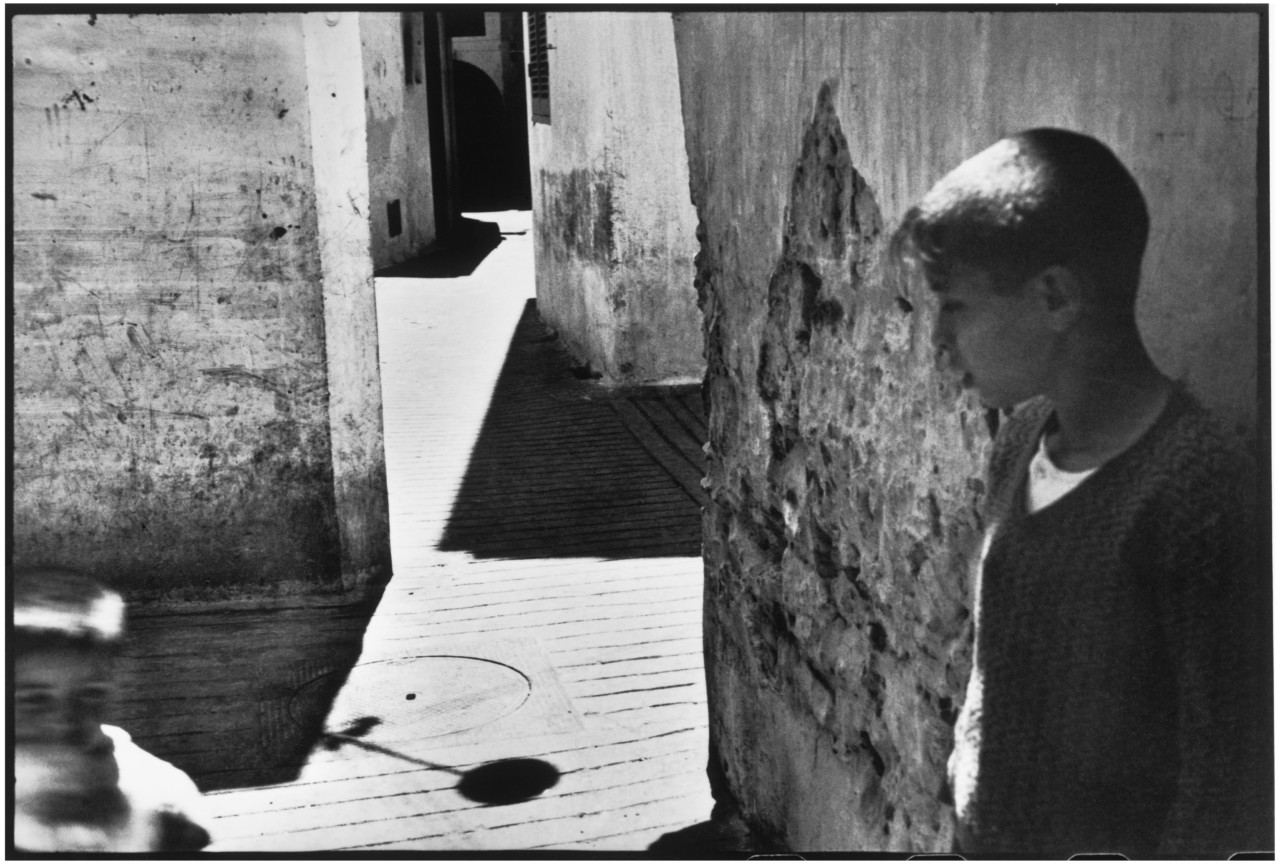

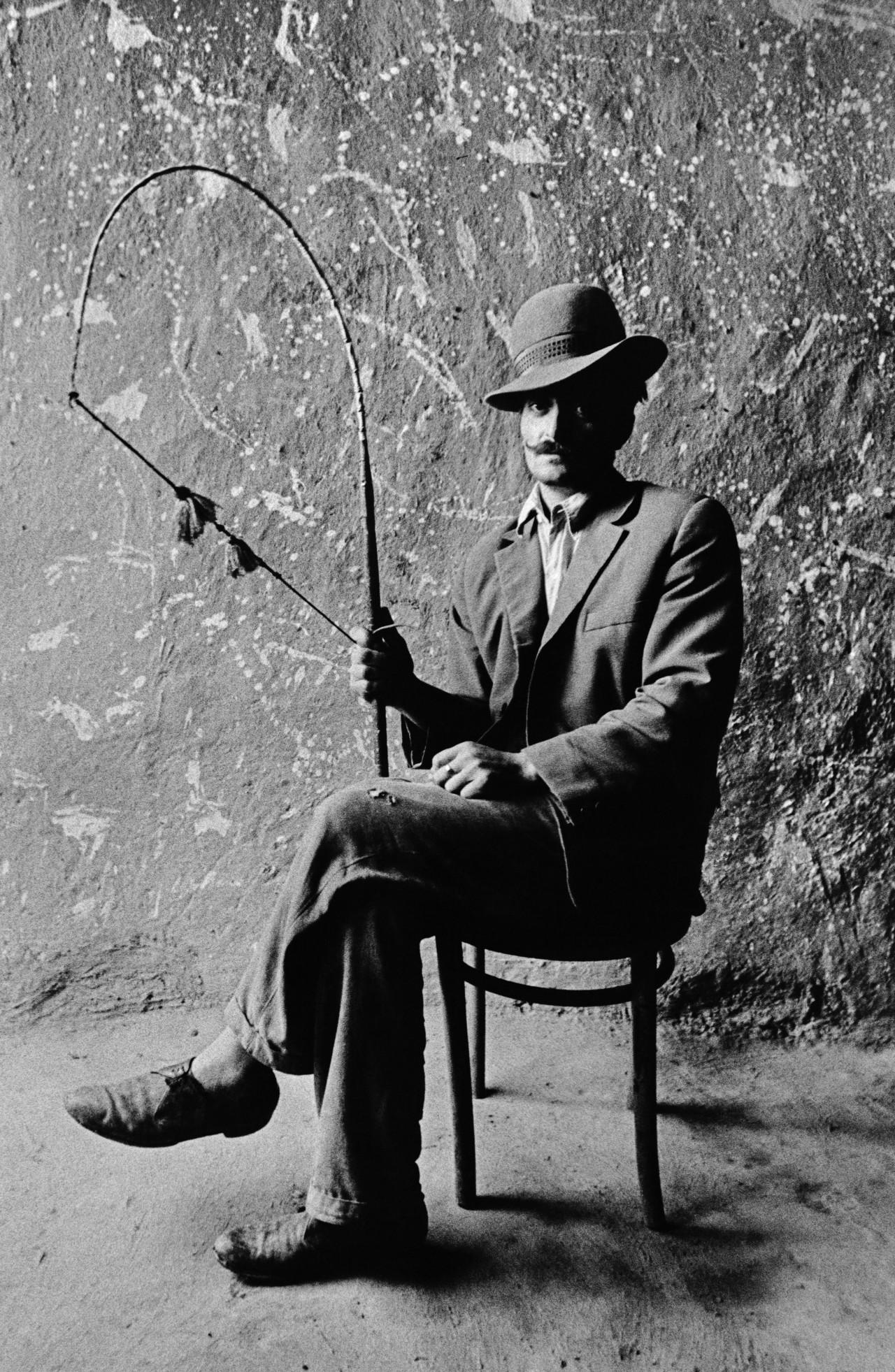

Visual poetry is a kind of catch-all where ambiguity is enhanced by a sort of lyricism that defies explanation. Henri Cartier-Bresson’s 1933 photograph of a boy standing in Seville’s narrow back streets surrounded by triangular shadows and shapes, seems so perfect and complete as a photographic composition. As does Josef Koudelka’s lyrical 1968 photograph of a man with a horse-whip, with its echoing curves, which carries no caption. As Koudelka once said: “I prefer people to look at my pictures and invent their own stories.” Do we need to know more from these authors than they are willing to divulge? I suggest not.

This is the larger question that I’m trying to unravel. Speaking to others, I have the sense that too much information can spoil the mystery. When I described the story behind Andrew Wyeth’s painting Christina’s World (1948) to a colleague, she seemed a little disappointed. I’d affected the magic. I think that’s the case with many of the photographs I’ve mentioned here. I have no burning curiosity to decipher the meaning behind the enigmatic smile in Elliott’s Siberian wedding picture. Oddly, I am curious about the man in Krass Clement’s Paris picture. I really would like to know why he’s carrying flowers, and for whom.

I am even more curious when it comes to emotional messaging. I find myself delving into biographies of artists and those of their muses to try to interpret every gesture. I did this with Édouard Manet, Berthe Morisot, and Patti Smith, and recently, on visiting the Modigliani show at the Tate, I found myself bewitched by a painting of Jeanne Hébuterne where the eyes are cold but the mouth is smiling.

Lastly, when it comes to reportage I welcome an explanation. Philip Jones Griffiths’s Vietnam Inc. (1971) is made special by its textual polemic and personal by the author’s analysis if the Vietnam War. Lorenzo Meloni’s photograph from Libya of the Murzuq desert (2015) seems to bridge the gap between visual ambiguity and extensive captioning. All approaches differ.

It’s clear that we are curious about the image, its context, and origination. But this is not always the case, and certainly not uniform. I find myself demanding more information of some images, yet welcoming the silence of other non news-related images. Herein lies the paradox of ambiguity; certainly, it is a topic to which we should pay more attention, in order to avoid the pitfalls of fake news.