The Changing Face of New York’s Little Italy

We reflect on the transformation of Little Italy as captured by Magnum photographers for more than 60 years

A number of images from this article are available as part of the newly expanded New York Collection of Fine Prints on the Magnum Shop.

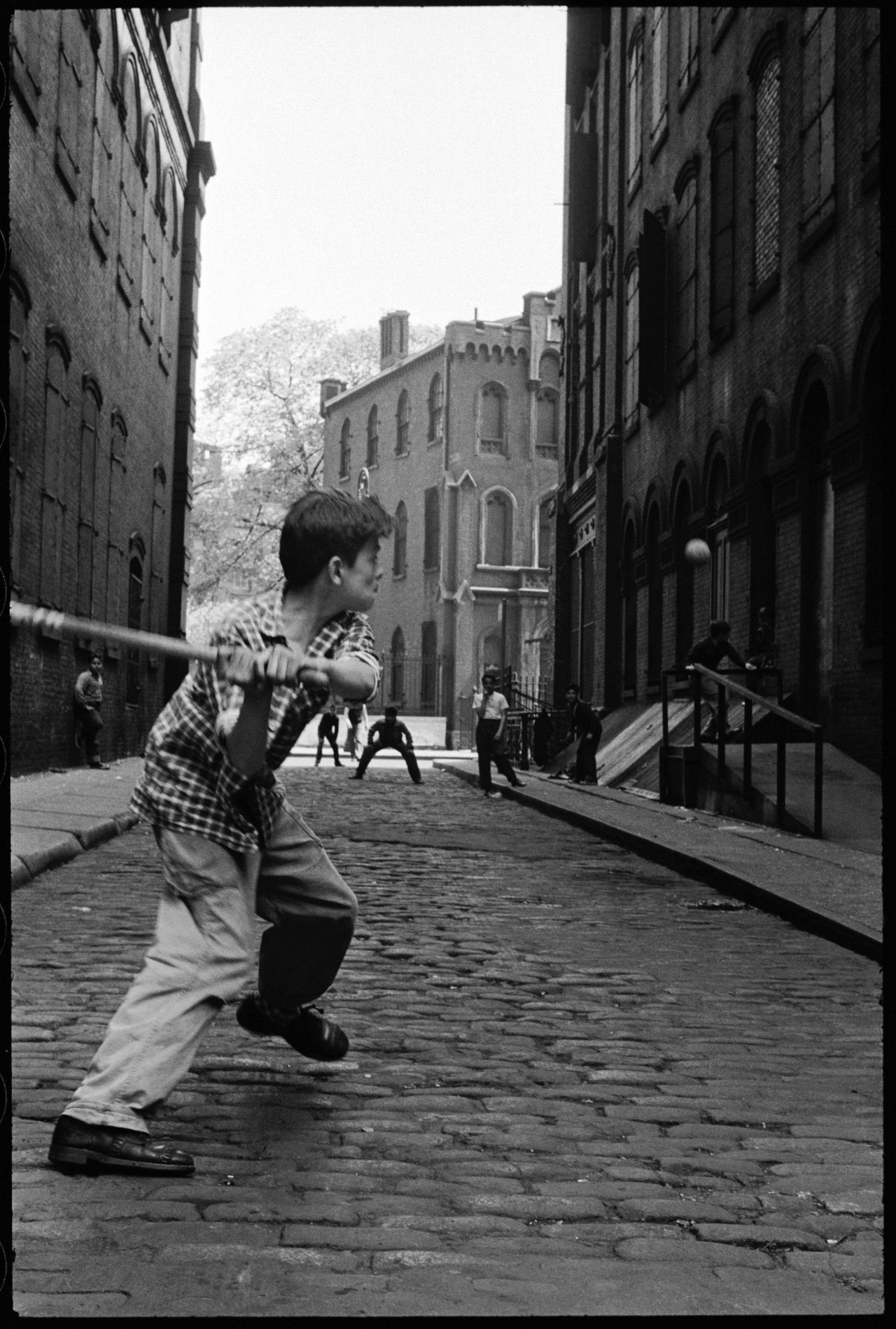

Little Italy, a neighbourhood in downtown New York City, was once a sprawling, cacophonous bustle of Italians who had left their homeland to capitalise on the promise of the American Dream.

Though they were not the only— or first—nationality to populate lower Manhattan’s tenement buildings, their vivid culture soon left an indelible mark. But as these photographs show, the scope and style of these streets—which have dwindled from 30 blocks to just three —has dramatically shifted since the first wave of immigrants arrived over two centuries ago.

The elegiac black and white of Leonard Freed’s photographs capture a time when horse and carts delivered laundry and a sharp suit and hat was la moda del momento. Freed, who referred to his relationship with Italy as a “love story”, lived in New York’s next best thing during the mid 50s. Freed was fascinated by this culture because, as Italian scholar Michael Miller wrote, “the past is always present in one form or another as people pursue their daily lives”. This theory is writ large in the family rituals and religious traditions that populate Freed’s frame.

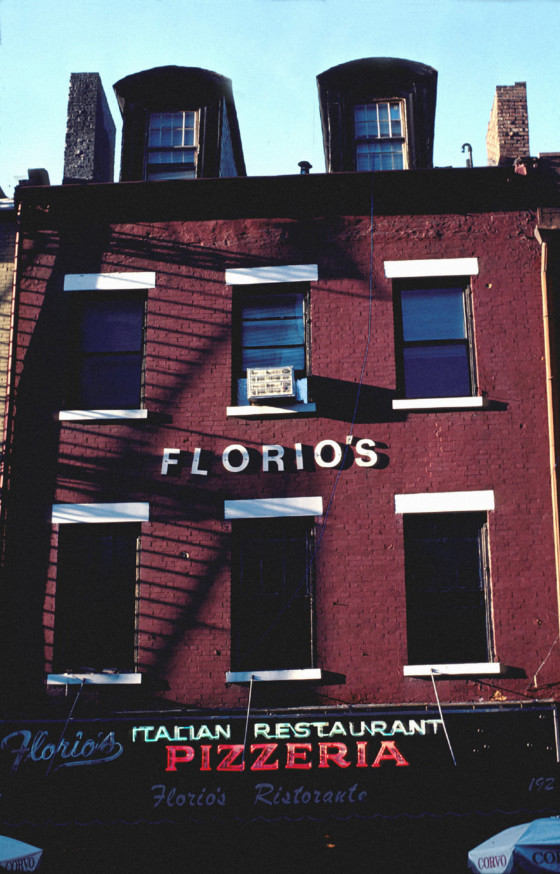

Big appetites are also synonymous with the Italian-American way of life and the annual Feast of San Gennaro Festival, which has been running in New York for more than 90 years, is a heightened display of this. Stuart Franklin, Ferdinando Scianna and Bruce Gilden were all drawn to this promenade of culinary passion, where a modern fusion of brash American neon and bold Italian flavours coalesce.

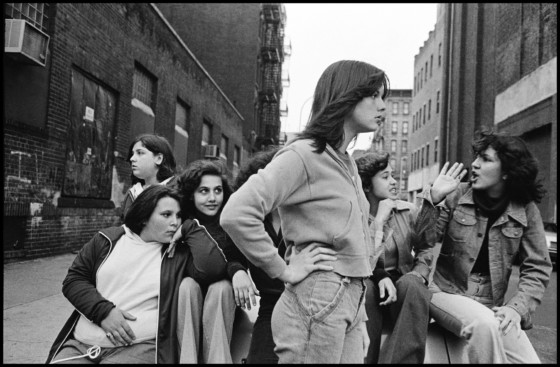

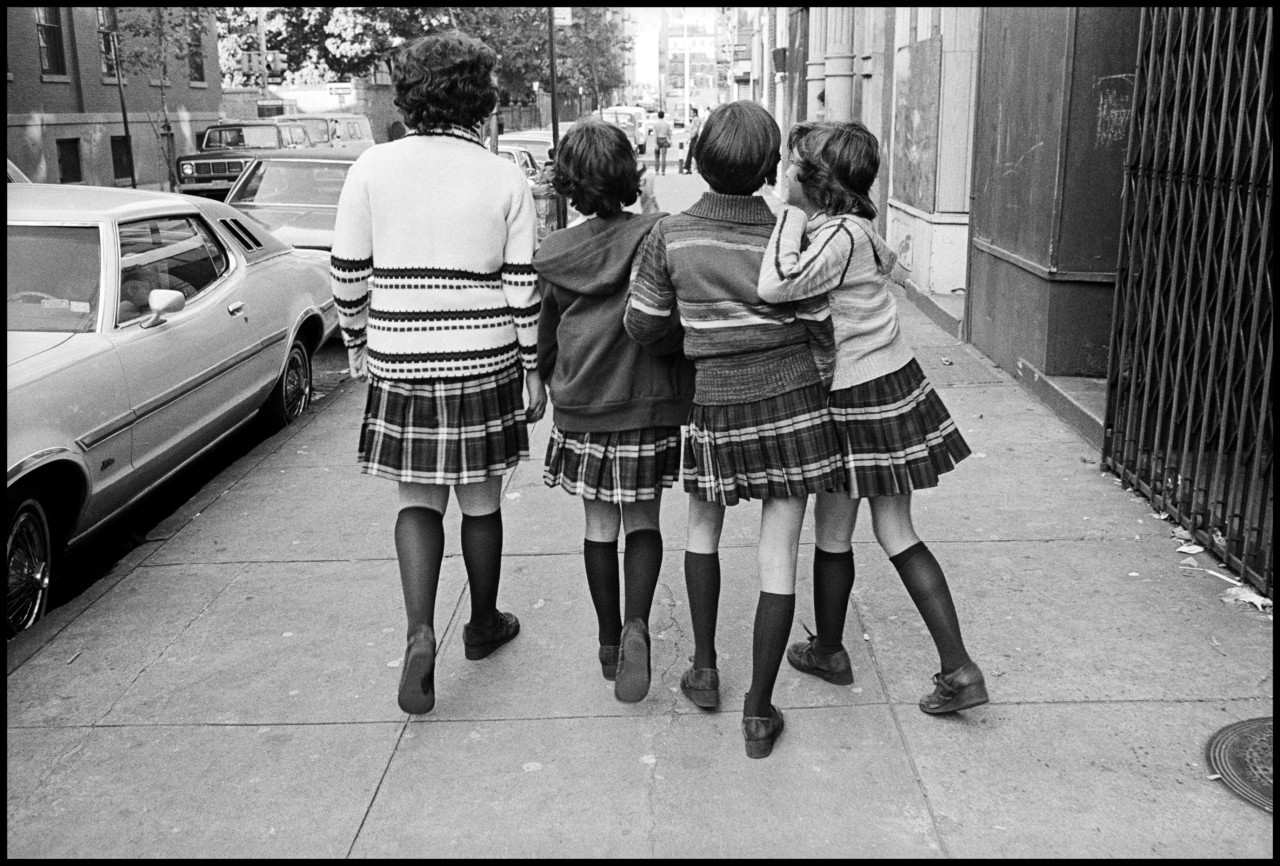

But while cultural tradition was part of what made the area thrive, it was the small stories of its unassuming residents that left just as much of a mark. Between 1975 and 1979, Susan Meiselas photographed a group of young Italian-American women who used to hang out on a corner near Prince Street almost every day.

“I was the stranger who didn’t belong,” said Meiselas, of that time. “Little Italy was mostly for Italians then. The girls were from small Italian-American families and they were almost all related.” Her series, Prince Street Girls, not only captured the young women’s passage into adulthood but also reveals the shifting borders of Little’s Italy’s gentrification, which was already under way even then.

Now, Little Italy is little, not very Italian and mostly patronised by tourists, though a whisper of the old world can still be found in the storied walls of Angelo’s of Mulberry Street, established in 1902, or Caffe Roma, which has been serving pastries and coffee for nearly 130 years. But Freed’s vision of white weddings, communion and community has disappeared and Meiselas’ Prince Street Girls—along with almost all of the old Italian-American families—are long gone.