Making the Image: Susan Meiselas’ Carnival Strippers Contact Sheet

The photographer explains how a dialogue with her subjects forged access to their personal lives, and led to the making of some of the best-known images from her first major work

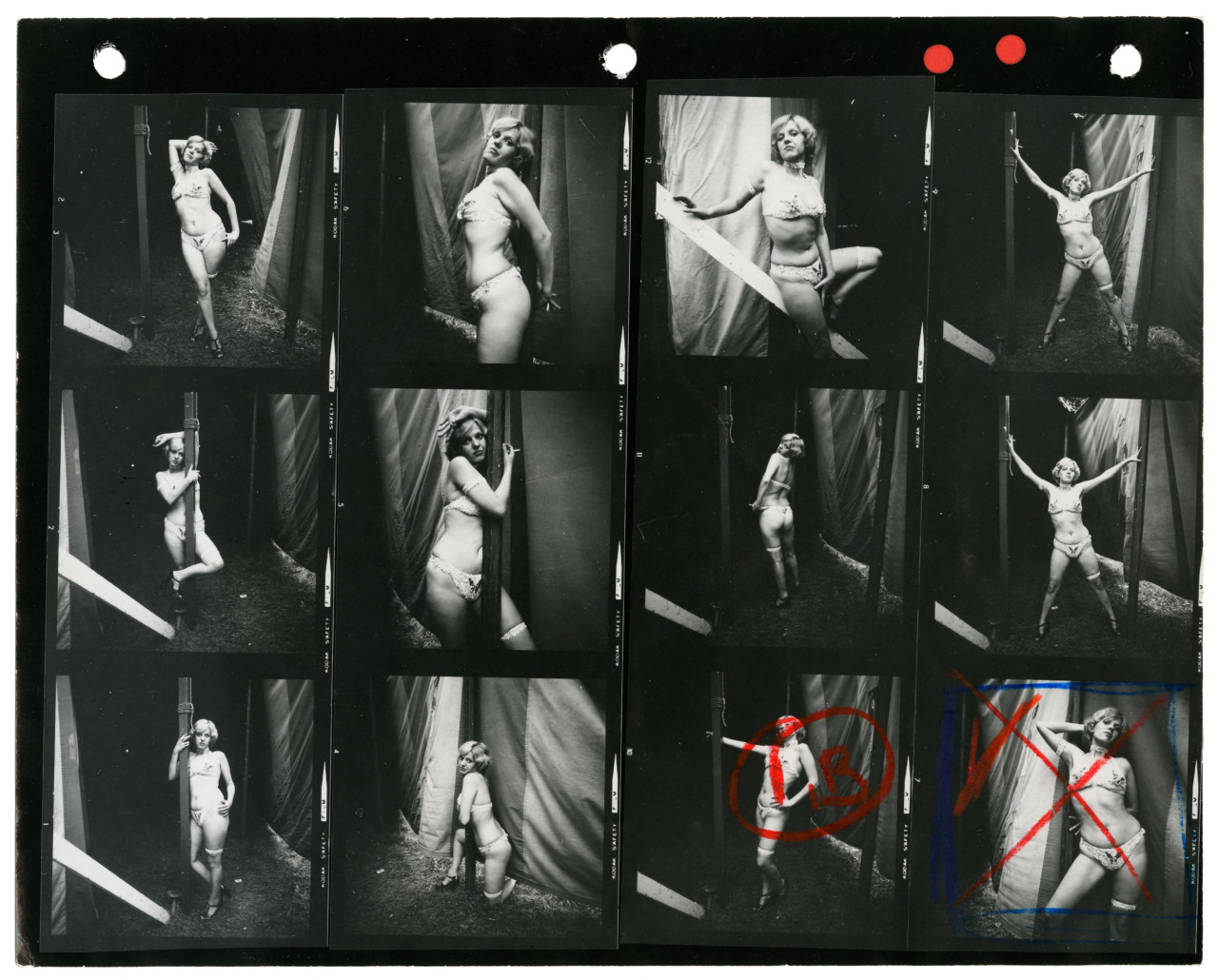

Contact sheets: direct prints of sequences of negatives were – in the pre-digital era – key for photographers to be able to see what they had captured on their rolls of film. They formed a central part of editing and indexing practices, and in themselves became revealing of photographers’ approaches: the subtle refinements of the frame, lighting and subject from photograph to photograph, tracing the image-maker’s progress toward the final composition that they ultimately saw as their best. There is a voyeuristic aspect to looking at a contact sheet also: one can retrace the photographer’s movements through time and space, tracking their eye’s smallest twitches from left to right as their attention is drawn. It is as if one were inside their head, offered a privileged view through their very eyes from the front row of their brain.

As Kristen Lubben wrote in her introduction to the book, Magnum Contact Sheets, first published in 2011 by Thames and Hudson:

“Unique to each photographer’s approach, the contact is a record of how an image was constructed. Was it a set-up, or a serendipitous encounter? Did the photographer notice a scene with potential and diligently work it through to arrive at a successful image, or was the fabled ‘decisive moment’ at play? The contact sheet, now rendered obsolete by digital photography, embodies much of the appeal of photography itself: the sense of time unfolding, a durable trace of movement through space, an apparent authentication of photography’s claims to transparent representation of reality.”

You can read other entries in Magnum’s series on contact sheets, and the making of iconic images here.

From 1972 to 1975, Magnum photographer Susan Meiselas docuemnted the women who performed stripteases at small-town carnivals in New England, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina – both photographing them and conducting interviewings. As she followed these carnivals from town to town, Meiselas portrayed the dancers both on stage and off, capturing their public performances as well as their down-time and private lives. Below, we reproduce Meiselas’ entry from Magnum Contact Sheets, in which she describes forging relationships with the performers, and the value of buidling a dialogue with one’s subjects.

“In 1972, my partner Dick and I spent our first summer together and wanted to take a road trip. We decided to follow small circuses in the Midwest and ended up at state fairs and then carnivals in New England. I wasn’t looking for the girl shows, until I found them.

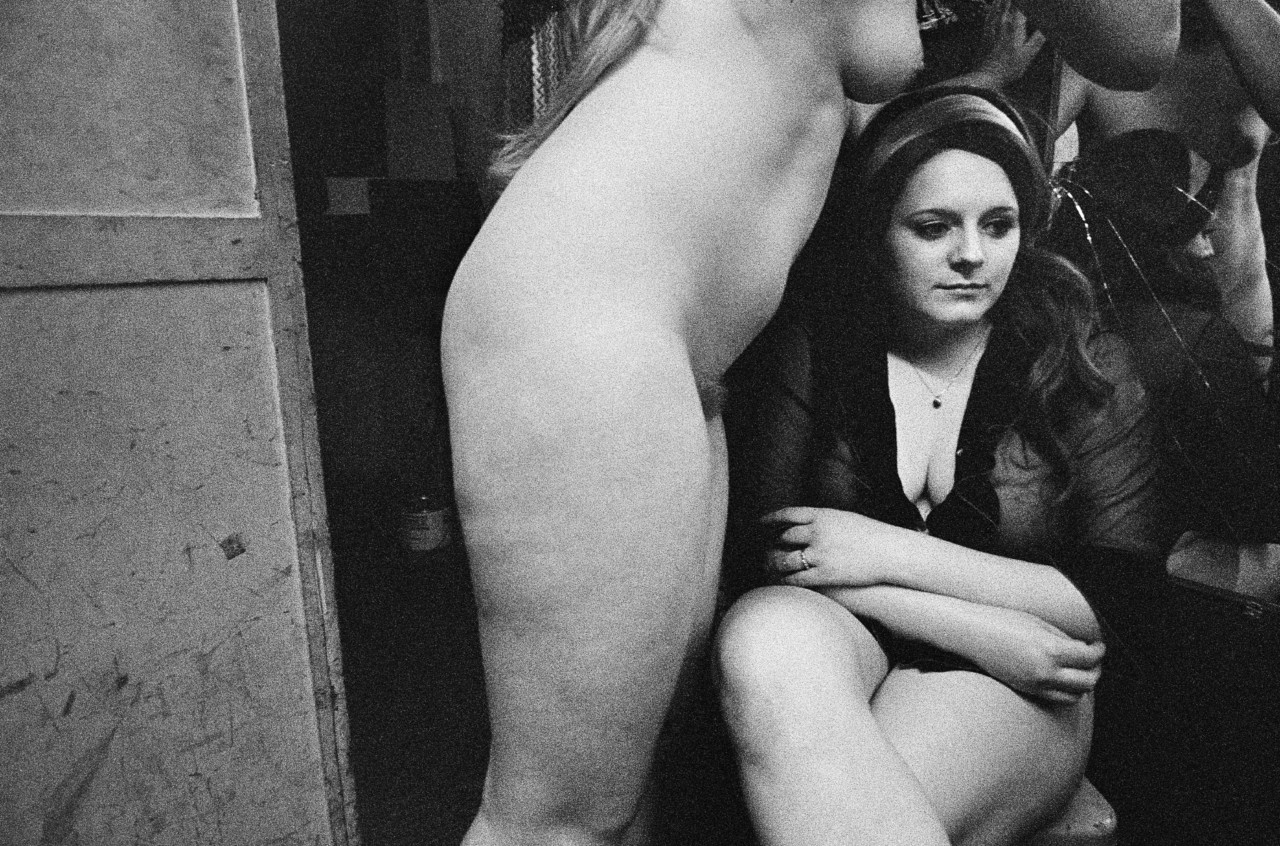

The work was done over three summers, each one building off the last. A publication called Variety would list the fair dates before the season began. I figured out which carnivals were carrying girl shows and who would be where. Weekend to weekend, the shows travelled from Maine, through New Hampshire, to Vermont. The first summer I photographed from the fairgrounds, I was like everyone else walking by and watching. When I decided to return the second summer and follow the full route of the show, starting in Maine, I began to forge relationships and eventually it was through the women’s invitations that the managers allowed me into the dressing rooms. Each weekend some girls rotated out, but enough of them – or at least one – would feel comfortable enough to invite me inside. I chose the classic fly-on-the-wall approach. I’m sure the girls were very aware of my presence, but I felt invisible. I made these photographs with a handheld Leica, no flash, and instead a long shutter speed and wide-open lens. The weeks of being with the women, changing locations each week, setting up the show, enduring long rainy nights, hoping there would be an audience, standing by them in difficult moments – all were factors in gaining their trust.

Issues of continuity were very problematic. I would sometimes take a portrait of a woman, bring the photograph back the following week, and she would have disappeared to go off with a boyfriend or just quit.

Still, I processed the film weekly so that the girls could see the contact sheets if they returned to the show or if I could find the show when it travelled to the next spot. Sometimes I would bring a few prints, but mostly the contact sheets. The value of that was the dialogue: they essentially saw all that I was shooting. They would mark with an initial if there was a particular picture they wanted, but most of the time they chose portraits, which is really why I began to shoot formal, medium-format portraits in addition to the backstage 35mm. In some shots they really performed for the camera with a pose. I felt awkward directing them in any way. I think you can feel that in the portrait encounters; they simply performed themselves or perhaps presented what

they thought showgirls should look like for me.

I met Lena on the first day she arrived to get a job at the girl show near her home town in Damariscotta, Maine. The second portrait shown here is long after that ‘first day’. She’d worked the shows for three summers; her body revealed the wear of those years. She was astoundingly articulate and open to sharing her feelings. She at times expressed alienation or sudden ecstasy. She was defiant. She challenged the managers, both male and female, and was erratic in her moods when performing. I wanted my photographs of her to convey her complexity. We knew each other over many years. When her mother sent me a letter saying she had died of an overdose, it was just after I’d been photographing the insurrection in Nicaragua (1978–9). There I had seen a very different kind of death. The idealistic Sandinista slogan was Patria libre o Morir (‘a free country or death’). I was in the midst of covering this phenomenally collective, enveloping movement, and in contrast Lena seemed so isolated and alone.”