Kurdistan: A Family Album

Susan Meiselas’ work on the Kurdish people’s historic, and ongoing, struggle for statehood

Magnum photographer Susan Meiselas’ retrospective show ‘Mediations’ is one of four bodies of work shortlisted for the 2019 Deutsche Borse Photography Foundation Prize. ‘Mediations’ drew on Meiselas’ work spanning four decades, and included projects like Prince Street Girls and Carnival Strippers, as well as her reportage on Nicaragua’s insurrection and revolution spanning 10 years, and her longterm work on the Kurds, which became the book Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History.

Described by New York Times reviewer Karl E. Meyer as a ‘family album of a forsaken people’, the project saw Meiselas create a visual archive of the Kurdish peoples’ struggle for nationhood through her own interviews and photographs as well as collected historical, ethnographic, and personal images. Christopher Hitchens, in the Los Angeles Review of Books wrote that, “Susan Meiselas has, with infinite labor and tenderness, composed a collage, framed a composition, designed a frame, confected a design and by means of a deft balance between text and camera, brought off a thing of beauty as well as instruction…”

Meiselas’ Kurdistan project is on show at The Photographer’s Gallery in central London, until June 2, as part of the Deutsche Borse exhibition. Here, we reproduce Meiselas’ introduction to Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History, alongside a selection of the book’s images.

Qala Diza, Northern Iraq: April 1991

At every mountain pass, another village leveled; stone houses are now piles of rubble. No electricity, no running water, little food. People living under slabs of concrete within the ruins of their former homes. They have chosen to stay in this wasteland rather than face exile in either Turkey or Iran.

When the Gulf War began, I, like most Americans, knew little about the Kurds. My first visit to the region was brief. Pleased to have the Western press witness the Kurds’ pressing need for humanitarian aid, Iran facilitated access to the Kurdish refugee camps. I was given a five-day visa—barely time to leave Paris, cross the Iranian border, and get to the “liberated” zone within northern Iraq. While the world’s attention was concentrated on the flight of the Kurds, I was drawn to the places from which they’d come. I drove in along the same road upon which many Kurds were still fleeing. I was stunned by what I saw.

I had never witnessed such a complete and systematic destruction of village life, even in ten years of covering the conflicts in Central America.

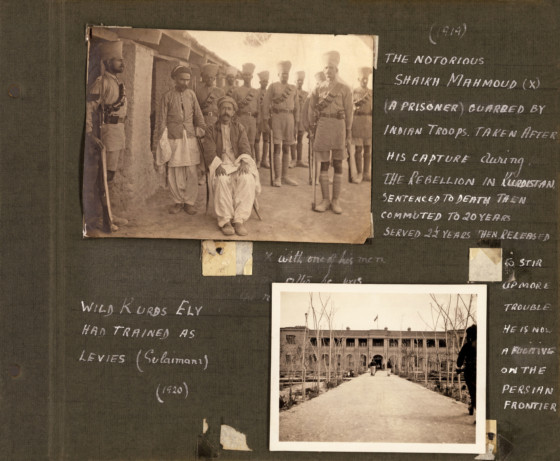

Although few Western observers had been inside northern Iraq for nearly a decade, reports periodically leaked out through the Kurdish network about Saddam Hussein’s 1988 “Anfal” campaign, a brutal attempt at annihilation. Nearly 100,000 Kurds were said to have “disappeared.” After reports that mass graves had been uncovered inside the Kurdish enclave, the group Human Rights Watch sent a mission into the territory to investigate. It was an opportune moment, since no one knew just how long it would take Saddam to regain military strength and reassert control over the region.

I was asked to join Dr. Clyde Snow, a forensic anthropologist well known for his exhumation of the mass graves in Argentina and Chile. My task was to photograph the sites of evidence—scars on survivors, unmarked graves, the clothes that had once wrapped bodies now buried anonymously, the bullet holes in skulls—the visible remains. That the Anfal campaign had ended three years before did not reduce the urgency with which we worked. I was part of an international team building a legal case against Saddam Hussein’s brutality. Working with a small group of Kurds, we excavated where the gravediggers remembered burying the dead. Meticulously, earth was shoveled and then brushed away by hand, until finally the skull of a male teenager appeared, a synthetic cloth blindfold still wrapped around it. Needing no instruments, the experienced Dr. Snow measured the holes to determine range, caliber, type of weapon. He concluded that the boy was the victim of an execution.

These were not the first mass graves I had documented. This time, however, I was coming in at the end of the story. I had no connection to the Kurds and even less sense of why these killings had occurred. I felt strange—photographing the present while understanding so little about the past. Now I realize that the unearthing of these graves led me to years of further digging.

"I felt strange—photographing the present while understanding so little about the past. Now I realize that the unearthing of these graves led me to years of further digging"

- Susan Meiselas

Paveh, Iran: September 1991

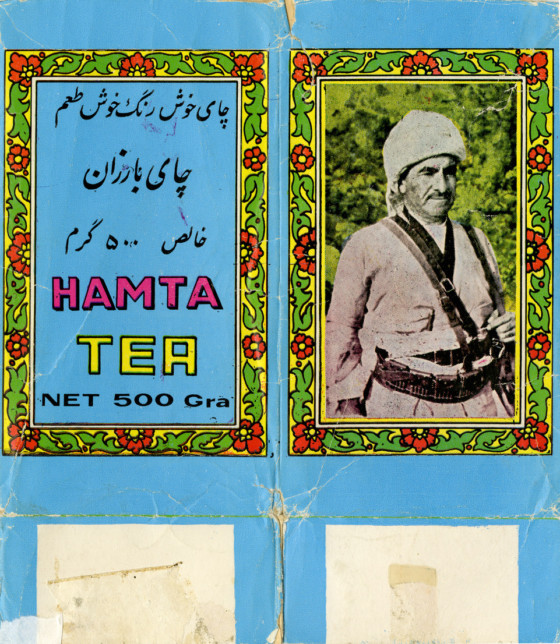

In the window of a small photo studio, there are typical pictures of the town’s weddings and recent births. Alongside the familiar is one image—quite horrific—of men bearing the impaled heads of Kurds on long spikes. I question the owner and am told that he does not know when the image was made or where he found it. Nor does he have any idea whose heads they were.

The studio owner, a Kurdish man, knows little about these events, yet he keeps the picture as a symbol of his people’s suffering, as a piece of the past, as evidence of a history. Not knowing quite why, I ask if I can make a copy of the print. I am struck by the role of the local photographer—as keeper of the collective archive—reproducing an image from his world to share with a total stranger.

Today “Kurdistan” does not exist on the map. Since 1918, the Kurds’ homeland has remained divided among Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Syria, and what is now the former U.S.S.R. In each country the Kurds have been continuously threatened with either assimilation or extermination. But as a place, Kurdistan exists in the minds of more than twenty million people, the largest ethnic people in the world without a state of its own.

An isolated image in a window would seem to pose little threat, but that local shopkeeper is surely a man of courage. An accessible repository of Kurdish images is impossible anywhere in the Middle East. It is no accident that the Kurds do not have a national archive.

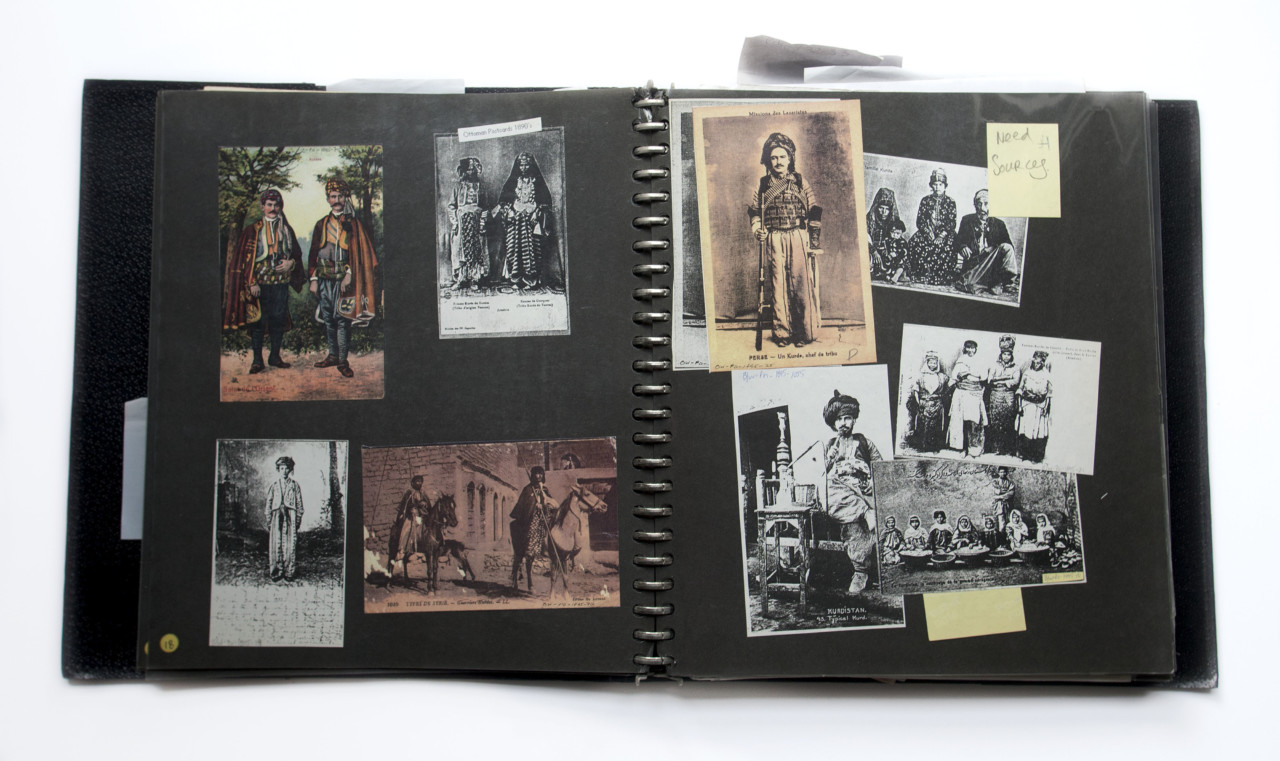

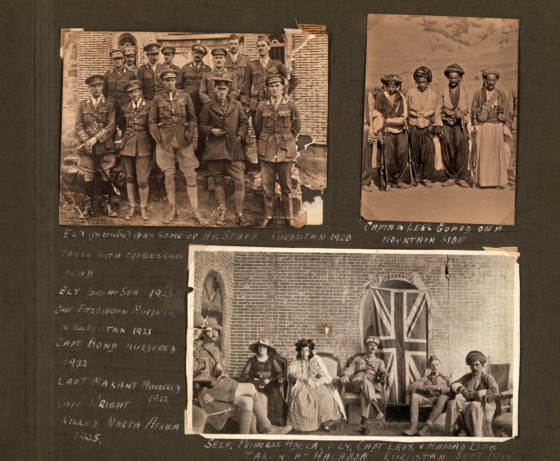

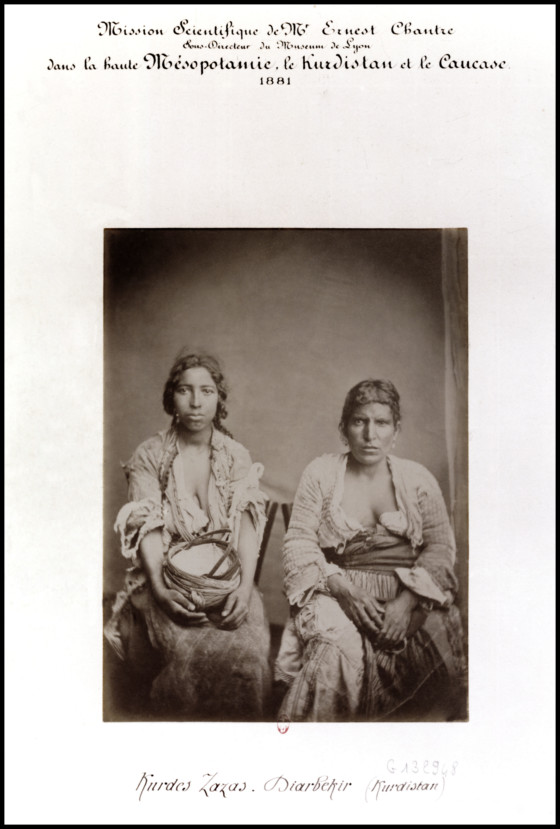

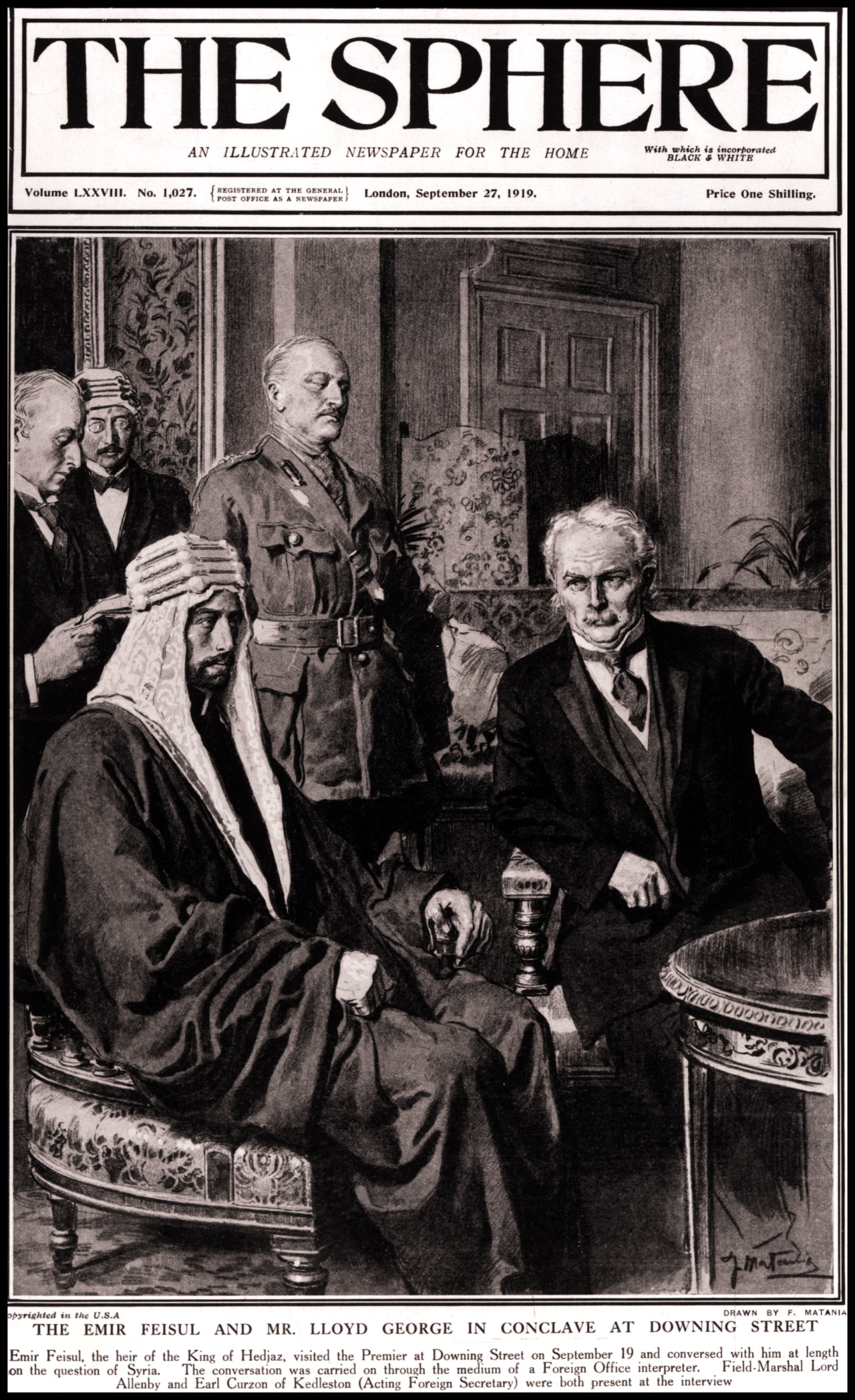

Some Kurds know a lot about those who passed through their lands over the last century. The names of Western travelers, missionaries, military officers, and colonial administrators float among the names of their own Kurdish heroes. My friend Bakhtiar Amin told me about a Major Noel, who in 1919 advised the British to be careful to distinguish between the Kurds and their Middle Eastern neighbors. Though Noel’s diary could be found in the Public Record Office in London, it has only recently been published in Kurdish. Other Kurds told me that they had read some of the Western memoirs written about them. Dusty books, sparsely illustrated, long out of print, were taken off back shelves in their homes and proudly shown to me as treasured accounts. Thumbing through the pages, I thought about all the photographs that had been made and then taken away from Kurdistan.

I, too, have been such a traveler. I began to wonder where those early photographs were, imagining the route of their travel—carried by hand as glass or nitrate negatives, or shipped in trunks—to be pasted into albums or relegated to archives, or to disappear into attics. I wanted to retrace the paths of those earlier Western travelers and find the souvenirs and recollections of their journeys.

New York City: September 1992

Archives are strange lands, each with its distinct organization. Photographs frequently inhabit files without record of date, name, place, or event. At the Bettmann Archive I am allowed to pour through the manila folders (the archive is not yet fully computerized). In the “Iran” folder, I find an image of a dignified man sitting on a chair placed on a carpet in the middle of a stark landscape, men in Kurdish dress behind him. This picture could never have been discovered without browsing—its caption identifies him as a general but makes no reference to the Kurds.

Finding a photograph is often like picking up a piece from a jigsaw-puzzle box with the cover missing. There’s no sense of the whole. Each image is a mysterious part of something not yet revealed.

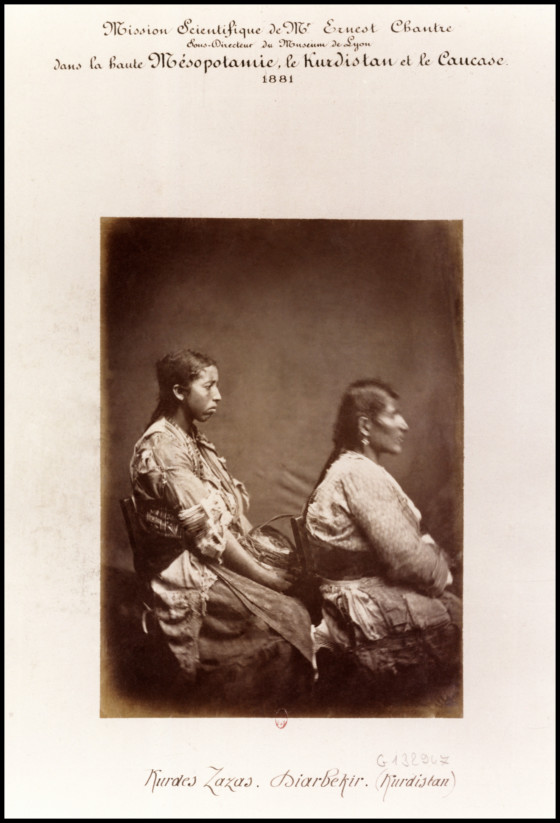

In Western archives, the word “Kurdistan” is rarely indexed. The Kurds are cataloged according to the countries in which they live as minorities; most often they appear in archival indices as “ethnic types.” In each collection the classification varies; the photograph is seen as ethnographic description or aesthetic object, especially if it was made by a renowned photographer. Rarely is there any historical information about the people who are pictured and then categorized. But the image still stands as evidence of an encounter.

Every picture tells a story and has another story behind it: Who’s photographed? Who made it? Who found it? How did it survive? I wonder what we can know of any particular encounter by looking at such a picture today. We have the object, but it exists separated from the narrative of its making.

What interested me was the intersection and interplay between those who shaped Kurdish life and the lives of the chroniclers who pictured them—the photographers and those photographed, the points of cultural exchange, how the various protagonists crossed one another’s paths. Both left their marks on Kurdish history.

"I thought about all the photographs that had been made and then taken away from Kurdistan.

"

- Susan Meiselas

Diyarbakır, Turkey to Arbil, northern Iraq: October 1992

Crossing the border again into Iraq, this time to travel with As’ad Gohzi, a former peshmerga fighter who is not just a translator but truly a guide. Within bare rooms, men sit on carpets with their backs against walls, drinking tea; the women are hidden, along with their stories. Only because we are Western women are we welcome to join the men.

As’ad knows whom to approach and how to appreciate the gracious and extended Kurdish rituals. Custom requires celebrating our visit with a meal. Several hours later, the photo albums and bags full of pictures appear from the closets, evoking spontaneous memories. Teaching Kurdish history and language is illegal in schools throughout Turkey and Iran. So stories passed down within families carry much of what is known about the past, preserving it for generations.

I can’t escape the tradition of the colonial foreigner. I travel and collect, take and treasure, classify, consume and possess. Yet I also feel the need to repatriate what I uncover as I attempt to reconstruct the past from scattered fragments.

With photocopies of pictures from Western archives, my assistant, Laura Hubber, and I returned to northern Iraq. We moved from house to house seeking assistance in the identification of a familiar face, a facade, or simply the date that a costume or custom might disclose. We annotated as we went. With As’ad, we first visited the homes of powerful aghas and shaikhs and then began to trace the genealogies of families known to have played important roles in Kurdish nationalist history.

Over time, my role divided between maker and collector. I stopped taking photographs, except to reproduce existing family photos with a Polaroid system. I felt immense pleasure sitting with families, first peeling off a positive image (the back of the print served as a perfect reference card for notations), then watching with my host as the negative appeared in the tray of sodium solution. Their precious originals stayed with them, but they allowed us to make copies to take away. These were privileged moments: to be invited inside, to listen to the storytellers, then to eat and sleep on their floors. Everywhere we were strangers, yet we were welcomed with trust as soon as people understood that they were contributing to a collective memory.

Arbil, northern Iraq: April 1993

A Kurdish scholar living in New York gave us the name of a well-known photographer, now dead. In Iraq, the photographer’s son greets us uncertainly, at first cautious about speaking of his patrimony. After tea, he disappears to the back of the house and returns carrying little orange boxes crammed with glass negatives. He shows us what remains of his father’s distinguished work.

Making prints is complicated logistically and must be done discreetly. We borrow a small darkroom in town, mix homemade chemicals, and use paper I’ve brought from New York. Formal portraits of families and notables, private and public events appear. One image leaps out: a group of Kurds behind someone in official dress, the Persian flag hanging above them. A significant moment—a brief interim before power became centralized in Persia? An image suggesting the hope that Kurds could control their ancestral lands? Or does this photograph memorialize yet another lost possibility, tribal chieftains betraying other rival chiefs? There’s no way to know yet.

After I finish printing, the photographer’s son reburies the glass plates somewhere in his backyard, to make sure that whatever might happen in Iraq, the images will somehow survive.

Our next few trips were driven by active pursuit—to try to rephotograph those pictures too dangerous for the Kurds to carry across any borders. Even a family portrait can be considered subversive if interpreted by officials as an expression of Kurdish identity and thereby linked to a nationalist movement. Of the nearly half million Kurdish refugees now living in Europe, I wonder how many of them had to leave their photographs behind.

As military operations intensified in the Kurdish provinces of Turkey, I wanted to pick up my camera and shoot or at least witness what was happening—villages being burned and thousands of Kurdish families forced to evacuate. But mobility in the area was restricted: journalists—especially photographers—were obliged to report to local authorities and were not permitted to wander. The Kurds could no longer afford to talk to strangers or speak about a history that had long been publicly denied.

Eventually, the Turks closed the border with northern Iraq, cutting down the flow of nongovernmental workers and limiting visas for the foreigners who had previously crossed freely. This meant that I could not photograph in the “militarized zone” or continue to collect anywhere in Kurdistan. The only possibility was to resume research in the archives and to keep up the work within the exile community.

New York City: June 1993

People keep sending material. A package arrives from the grandson of Percival Richards, who accompanied Major Noel to Kurdistan in 1919. Heaped together with the pictures are a few letters scribbled in pencil by Richards to his wife, along with his marriage license, a passport, and the bill for his coffin, detailing its size and cost—a man’s life now contained in a yellow plastic bag. My studio is filled with stacks of images made by men and women whom I’ve never met, most of whom died before I was born.

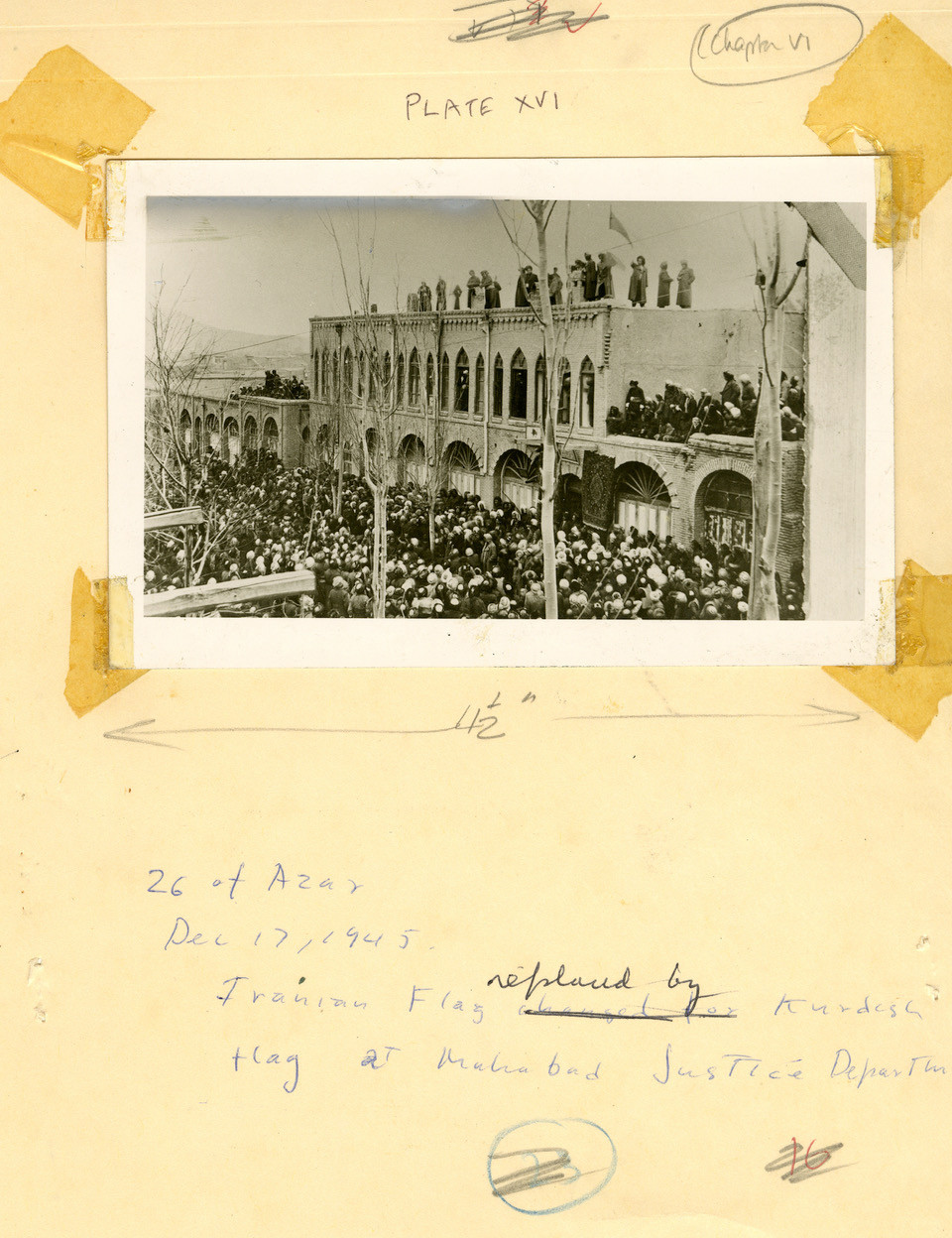

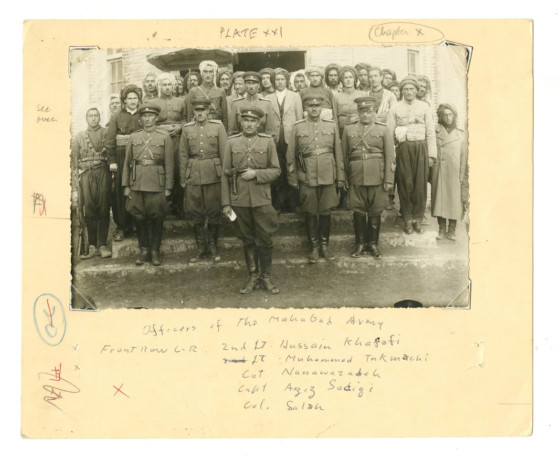

New York City: September 1993

There’s a book in the library, The Kurdish Republic of 1946, detailing the brief moment in history when the Kurds had an independent state. Within a year, the Iranian army attacked the central city of Mahabad. The Kurds destroyed all their own records and photographs in fear of further reprisals.

I learn that the book’s author, William Eagleton, is now the special coordinator for the United Nations in Sarajevo. In the fifties he served as the American consul in Iran and collected interviews and existing documentation about the Mahabad Republic. I write to him, asking after the pictures that appeared in his book.

"For Westerners, I hope that this book can create a presence of those who continue to be distant, linking the headlines of the future with the Kurdish past.

For the Kurds, I hope that this book serves as a sourcebook of a suppressed history that can now be repossessed, though not without risk"

- Susan Meiselas

New York City: November 22, 1994

Received word from Eagleton—the Vienna warehouse where he’d stored all his papers has burned down. Everything has been lost except the pictures he sent us a few months ago. He writes, “I wish to know that they are safe, since they are the only things that remain of my adventures in Kurdistan.”

How arbitrary the survival of such evidence can be.

Most of the images and written artifacts about the Kurds that survive, survive in the West. In part this is because the Kurds have little security and limited funds to maintain museums and libraries or to protect private collections. Ironically, interpretations of their culture offered by outsiders—missionaries, colonial administrators, and early travelers—have become indispensable sources of written and visual information.

In the present work I’ve tried to re-create the Kurds’ encounter with the West and ask readers to engage in the discovery of a people from a distant place without knowing exactly where that process will lead.

In no way is this a definitive history of the Kurds. Texts and images are presented as fragments, to expose the inherent partiality of our knowledge. This is a book of quotations, with multiple and interwoven narratives taken from primary sources—the raw materials from which history is constructed.

Excerpts from diaries and documents make public what was often a personal record or private exchange. Suggesting the randomness by which history gets made, newspaper clippings and selected bits of memoirs reveal what was presented by the media and commonly believed at the time. Kurdish oral histories interspersed throughout contest the Western perspective of Kurdish life, as well as the view of the local regional powers. The book’s design reproduces the images with all the markings of age and travel, so that the surface itself reveals the history of survival. I emphasize the photograph as object, as artifact, once held, now torn and stained. A photograph is a document that resists erasure.

Rather than emerging as a completed puzzle with every piece fitting neatly together, this book project has revealed a mosaic—only from a distance is there a shape to discern. This is a reconstruction based on what remains and has been retrieved; we cannot know what is gone. Certainly, much is missing.

New York City: December 1996

A phone call just before Christmas day—As’ad Gohzi is in Guam. The U.S. military airlifted him out of northern Iraq along with other employees of U.S.-funded nongovernmental organizations who could be in danger if the Iraqi army returns. He arrived with his family and nearly five thousand other Kurds. The most recent round of infighting between the Kurdish parties triggered Saddam’s August invasion. Once again, families are ripped apart as the Kurds war among themselves.

New York City: July 16, 1997

Mustafa Khezry, with whom I first traveled to Iran, has just called. He has finally discovered the documents I wanted, in Baku, Azerbaijan. I think about my two earlier trips there. It was impossible for me to access the KGB files. I knew there was likely to be some material regarding the Russian relationship to the Kurdish Republic of Mahabad. I asked if there was anything about the deportations of the Kurds under Stalin. He couldn’t tell me.

It was hard to tell him that the book was going to press in two weeks’ time and that I couldn’t add anything else.

There will always be more to uncover.

In the same way that a collection of unearthed bones can reveal concealed events, these photographs cannot be denied. But like scattered bones, these images would have remained disconnected from the skeleton of the narrative without knowledge of the people and place from which they’ve come.

For Westerners, I hope that this book can create a presence of those who continue to be distant, linking the headlines of the future with the Kurdish past.

For the Kurds, I hope that this book serves as a sourcebook of a suppressed history that can now be repossessed, though not without risk.

—SCM

July 1997